- About

- Introduction

-

Browse the book

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- A >

- B >

- C >

- D >

- E >

- F >

- G >

- H >

- I >

- L >

-

M

>

- Main theories of power

- Making an effort is a prerequisite of using power

- Marxism and the meaning of power

- "May" power

- Meanings of power that are not directly related to social power

- Micropower: Individual power

- Mindfulness

- Media and Digital Literacy as Forms of Individual Power

- (Mis)understanding of power in media texts

- Money and Power

- My synesthetic perception of "power"

- N >

- P >

- R >

- S >

- T >

- U >

- V >

- W >

- Completed pages

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- Author

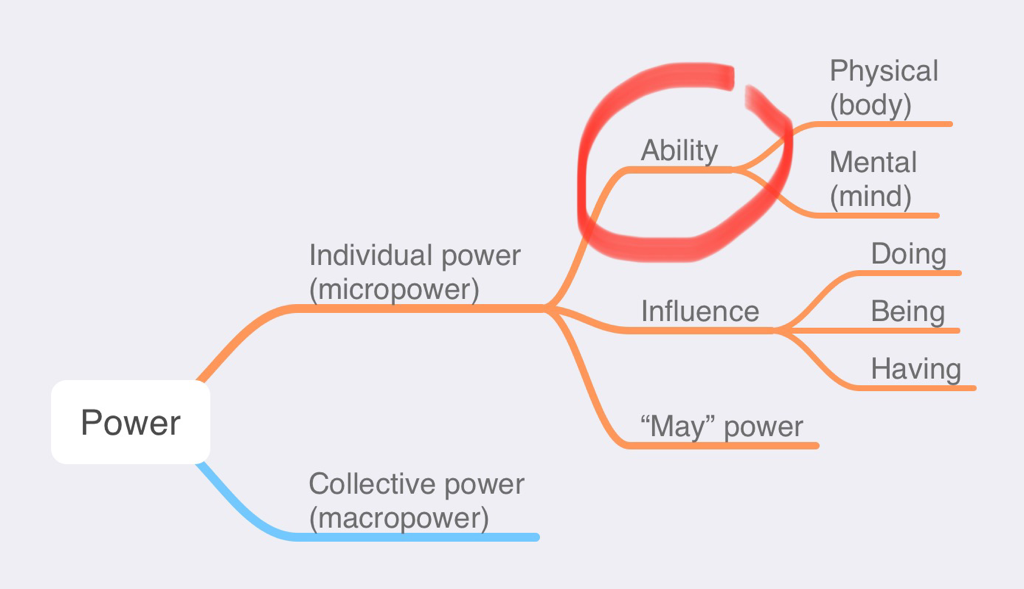

Power as Ability

(completed pages might be rewritten over time)

In some languages, the word power is related to ability (e.g., pouvoir in French and Macht in German). I will take this hint from language and explore what ability has to do with power. Ability is often introduced by the verb "can". As you will see below, this verb may refer to different kinds of power, as in the following statements:

It is important to note the following: power as ability complements power as influence, as these are two aspects of what I call micropower. The concept of micropower is meant to describe what happens on the level of individuals and specific interactions between them (as opposed to what happens at the macro level of society). Indeed, the four statements above describe qualities or situations that should be easy to imagine.

It is important to take a close look at power as ability because of how it relates to issues of responsibility and blame. As debates about social problems rage, it is not uncommon for participants to look for a guilty party: somebody who created a problem in question, although they could make different choices; somebody who keeps the problem going, although they could fix it. We should always ask ourselves, "Could they really?" and either give a clear answer or admit that we do not know.

Considering power as ability can help us better understand each other and manage our relationships. Here is a personal example: One day when I was still working on this entry, my 4.5-year-old son woke me up at 4:30 am in the morning. He could not go back to sleep and also kept me awake, although I told him that we will only get up at 6 am. I was angry at him until I asked myself: Can he really go to sleep? Can he really lay in bed quietly for 1.5 hours without disturbing me (by tossing, turning and sighing loudly)? Once I realized that the answer to both questions is "no", I was not angry at him anymore, and we had a nice morning together.

- "I can lift a heavy stone." [power of body]

- "I can understand the reasons for other people's actions, even if I dislike these actions." [power of mind]

- "I can calm myself down by slowing down my breath." [mind/body power]

- "I can tell my boss what I think about her, and she will not fire me." ["may" power]

It is important to note the following: power as ability complements power as influence, as these are two aspects of what I call micropower. The concept of micropower is meant to describe what happens on the level of individuals and specific interactions between them (as opposed to what happens at the macro level of society). Indeed, the four statements above describe qualities or situations that should be easy to imagine.

It is important to take a close look at power as ability because of how it relates to issues of responsibility and blame. As debates about social problems rage, it is not uncommon for participants to look for a guilty party: somebody who created a problem in question, although they could make different choices; somebody who keeps the problem going, although they could fix it. We should always ask ourselves, "Could they really?" and either give a clear answer or admit that we do not know.

Considering power as ability can help us better understand each other and manage our relationships. Here is a personal example: One day when I was still working on this entry, my 4.5-year-old son woke me up at 4:30 am in the morning. He could not go back to sleep and also kept me awake, although I told him that we will only get up at 6 am. I was angry at him until I asked myself: Can he really go to sleep? Can he really lay in bed quietly for 1.5 hours without disturbing me (by tossing, turning and sighing loudly)? Once I realized that the answer to both questions is "no", I was not angry at him anymore, and we had a nice morning together.

Image credit: Joseph Redfield

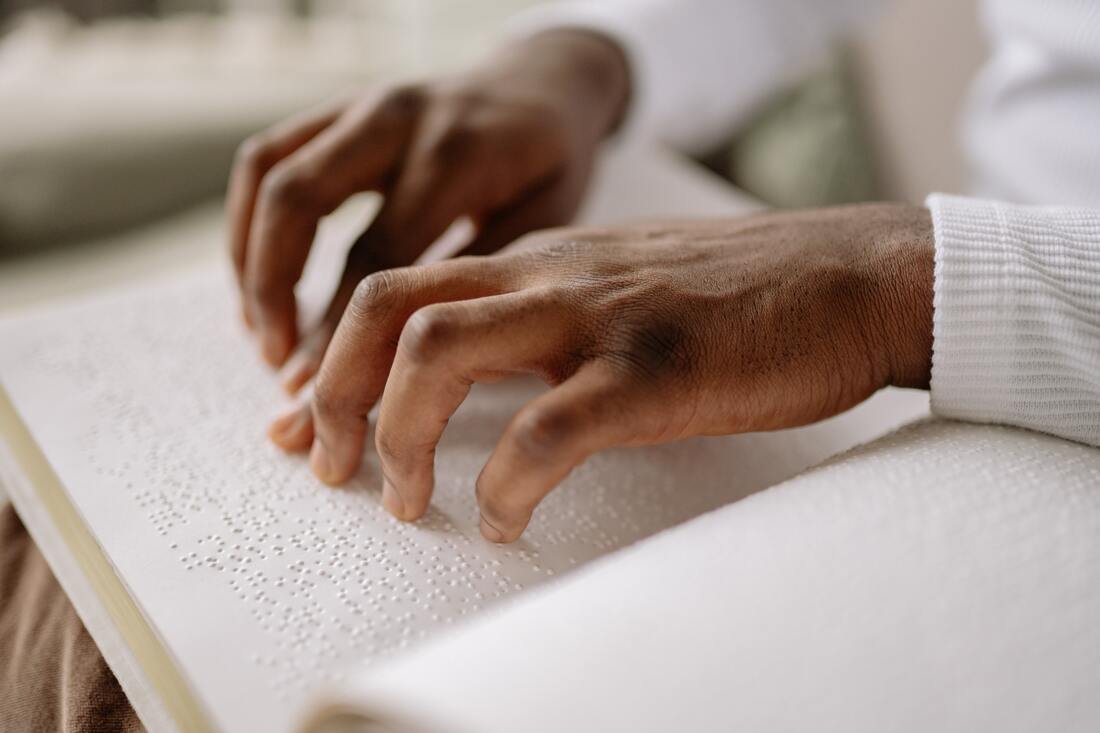

As I noted in the beginning of this entry, not everything that we call "ability" or introduce using the verb "can" is really a kind of power. It is important to distinguish between levels of the same ability; there is a difference between an ability as a function of our body (basic level) and the same ability used with intentionality (higher level). Intentionality is defined as "the fact of being deliberate or purposive". In other words, it is about making choices with a certain degree of awareness. So, basic level = my body can do (or even simply My body does) = not power; higher level = I can do = power. (The words "basic" and "higher" in this context are not used as an indication of value).

Seeing can be described as an ability; somebody who does not see well (and is beyond what glasses could fix) is usually called a person with a disability. Walking can be described as an ability; somebody who does not walk is usually called a person with a disability. However, if we consider seeing and walking on the most basic level, as functions of our bodies, they cannot be described as intentional. For example, if somebody forcefully keeps my eyes open, my eyes will see, no matter if I want to see or not. If I have functioning legs, they will move me around, even if I am just pacing my room. Power comes not just from having an ability as a function of one's body, but from making choices when using this ability.

Here is how intentionality is related to responsibility and blame: we cannot blame somebody for a function of their body, but we can hold a person responsible for intentionally using an ability in a certain way. However, the matter is complicated because boundaries between different levels of the same ability are blurry. Yes, I cannot not see if my eyes are open, but I do make choices about what I look at (and I also usually make a choice whether to have my eyes open in the first place). Yes, if my legs are functional I will use them to walk (if not, I will have serious health issues), but I do constantly make choices about where to walk (e.g., to a meeting) or how to walk (e.g., I can decide to walk slowly if I want to be late).

To complicate things further, some abilities as functions of our bodies are occasionally called "power". For example, the basic form of seeing is sometimes described as "power of sight", as in the following statement: "The power of sight is often taken for granted, but it greatly affects a person's quality of life". Notice that when we say “power of speech”, we refer to intentionally used ability and not just a body function. At the same time, such phrases as "power of walking" or “power of breathing” (breathing in general rather than in a certain way) sound strange. In the case of “power of sight”, we may be dealing with a quirk of language, a poetic expression rather than a rule (language throwing us off again).

As I noted in the beginning of this entry, not everything that we call "ability" or introduce using the verb "can" is really a kind of power. It is important to distinguish between levels of the same ability; there is a difference between an ability as a function of our body (basic level) and the same ability used with intentionality (higher level). Intentionality is defined as "the fact of being deliberate or purposive". In other words, it is about making choices with a certain degree of awareness. So, basic level = my body can do (or even simply My body does) = not power; higher level = I can do = power. (The words "basic" and "higher" in this context are not used as an indication of value).

Seeing can be described as an ability; somebody who does not see well (and is beyond what glasses could fix) is usually called a person with a disability. Walking can be described as an ability; somebody who does not walk is usually called a person with a disability. However, if we consider seeing and walking on the most basic level, as functions of our bodies, they cannot be described as intentional. For example, if somebody forcefully keeps my eyes open, my eyes will see, no matter if I want to see or not. If I have functioning legs, they will move me around, even if I am just pacing my room. Power comes not just from having an ability as a function of one's body, but from making choices when using this ability.

Here is how intentionality is related to responsibility and blame: we cannot blame somebody for a function of their body, but we can hold a person responsible for intentionally using an ability in a certain way. However, the matter is complicated because boundaries between different levels of the same ability are blurry. Yes, I cannot not see if my eyes are open, but I do make choices about what I look at (and I also usually make a choice whether to have my eyes open in the first place). Yes, if my legs are functional I will use them to walk (if not, I will have serious health issues), but I do constantly make choices about where to walk (e.g., to a meeting) or how to walk (e.g., I can decide to walk slowly if I want to be late).

To complicate things further, some abilities as functions of our bodies are occasionally called "power". For example, the basic form of seeing is sometimes described as "power of sight", as in the following statement: "The power of sight is often taken for granted, but it greatly affects a person's quality of life". Notice that when we say “power of speech”, we refer to intentionally used ability and not just a body function. At the same time, such phrases as "power of walking" or “power of breathing” (breathing in general rather than in a certain way) sound strange. In the case of “power of sight”, we may be dealing with a quirk of language, a poetic expression rather than a rule (language throwing us off again).

Image credit: Yan Krukov

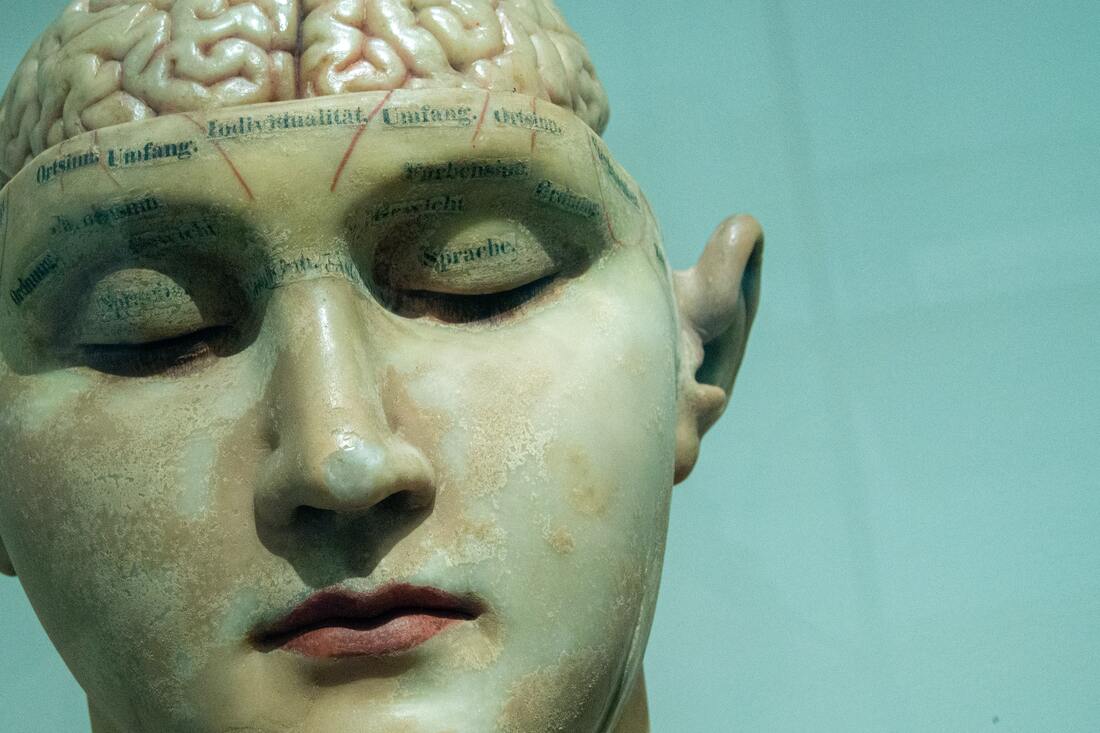

Now that I have clarified when an ability is power and when it is not, I will introduce four types of power as ability. As you will see below, this division is artificial, but it is helpful for the purpose of my analysis.

The three types of power as ability are "power of body", "power of mind", "mind/body power" and "'may' power". The division between power of body and power of mind is artificial because our mind is a function of the brain, which is a part of the body. Indeed, some abilities are better described as mind/body power. Power of body is mostly restricted to physical strength, hence the example "I can lift a heavy rock." Manifestations of power of body are usually visible, and outcomes can be easily traced to its application (if I see a mental rod before and after it has been bent, I know that somebody bent it).

In contrast, manifestations of mind/body power are less visible. In the example "I can calm myself down by slowing down my breath”, we can imagine an observer being able to notice how the breathing of the person making this statement changes (that's the body part of power), although they will not necessarily notice the calming down itself (the mind part of power), since signs of anxiety are not always external.

Finally, power of mind happens on a level that is completely hidden from an outside's observer's eyes. Even though direct outcomes of the power of mind can be visible, indirect outcomes are often hidden and difficult to trace back to the application of power. In the example, “I can understand reasons for other people's actions, even if I dislike these actions", the outcome can be me interacting with my adversaries in a certain way without explaining why I am doing that.

Perhaps because of its invisibility, power of mind is often misunderstood and valued less than power of body (by the same token, disabilities of the body are more visible and taken seriously than disabilities of mind). However, understanding how power of mind works is essential for making sense of society's flaws and dealing with them.

Now that I have clarified when an ability is power and when it is not, I will introduce four types of power as ability. As you will see below, this division is artificial, but it is helpful for the purpose of my analysis.

The three types of power as ability are "power of body", "power of mind", "mind/body power" and "'may' power". The division between power of body and power of mind is artificial because our mind is a function of the brain, which is a part of the body. Indeed, some abilities are better described as mind/body power. Power of body is mostly restricted to physical strength, hence the example "I can lift a heavy rock." Manifestations of power of body are usually visible, and outcomes can be easily traced to its application (if I see a mental rod before and after it has been bent, I know that somebody bent it).

In contrast, manifestations of mind/body power are less visible. In the example "I can calm myself down by slowing down my breath”, we can imagine an observer being able to notice how the breathing of the person making this statement changes (that's the body part of power), although they will not necessarily notice the calming down itself (the mind part of power), since signs of anxiety are not always external.

Finally, power of mind happens on a level that is completely hidden from an outside's observer's eyes. Even though direct outcomes of the power of mind can be visible, indirect outcomes are often hidden and difficult to trace back to the application of power. In the example, “I can understand reasons for other people's actions, even if I dislike these actions", the outcome can be me interacting with my adversaries in a certain way without explaining why I am doing that.

Perhaps because of its invisibility, power of mind is often misunderstood and valued less than power of body (by the same token, disabilities of the body are more visible and taken seriously than disabilities of mind). However, understanding how power of mind works is essential for making sense of society's flaws and dealing with them.

Image credit: David Matos

The last type of power as ability is what I call “may” power. It is exemplified by the statement, “I can tell my boss what I think about her, and she will not fire me”. This power actually exists at the intersection of power as ability and power as influence (suggesting that the division of micropower into ability and influence is also artificial).

Notice that the first three types of power as ability can be discussed as unrelated to other people’s abilities and actions. Our actions are, of course, always related to other people, because of the social nature of human beings. What I mean by saying that the first three types of power as ability are unrelated to other people's actions is that we do not have to imagine the role of other people in their existence. I can observe that somebody is physically strong without discussing how this strength may or does affect others, or how this strength is affected by other people.

But “may” power us impossible to describe without imagining other individuals and their actions. “May” power is introduced by the verb “can” as in the example above, but “can” here means “be allowed to”, which clearly indicates that a relationship between individuals (rather than properties of one individual) is described here.

Considering power as ability allows us to ask questions about sources of our power: Can everybody potentially learn to lift heavy stones? Can everybody potentially learn to slow down their breath in order to calm down? Can everybody learn to understand other people’s actions? Etc. These questions can help us complicate debates about responsibility and blame.

The last type of power as ability is what I call “may” power. It is exemplified by the statement, “I can tell my boss what I think about her, and she will not fire me”. This power actually exists at the intersection of power as ability and power as influence (suggesting that the division of micropower into ability and influence is also artificial).

Notice that the first three types of power as ability can be discussed as unrelated to other people’s abilities and actions. Our actions are, of course, always related to other people, because of the social nature of human beings. What I mean by saying that the first three types of power as ability are unrelated to other people's actions is that we do not have to imagine the role of other people in their existence. I can observe that somebody is physically strong without discussing how this strength may or does affect others, or how this strength is affected by other people.

But “may” power us impossible to describe without imagining other individuals and their actions. “May” power is introduced by the verb “can” as in the example above, but “can” here means “be allowed to”, which clearly indicates that a relationship between individuals (rather than properties of one individual) is described here.

Considering power as ability allows us to ask questions about sources of our power: Can everybody potentially learn to lift heavy stones? Can everybody potentially learn to slow down their breath in order to calm down? Can everybody learn to understand other people’s actions? Etc. These questions can help us complicate debates about responsibility and blame.

If you are interested in getting updates about this project (e.g., when new pages are published), please sign up for the newsletter on my main website.

THIS WEBSITE CONTAINS NO AI-GENERATED CONTENT

- About

- Introduction

-

Browse the book

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- A >

- B >

- C >

- D >

- E >

- F >

- G >

- H >

- I >

- L >

-

M

>

- Main theories of power

- Making an effort is a prerequisite of using power

- Marxism and the meaning of power

- "May" power

- Meanings of power that are not directly related to social power

- Micropower: Individual power

- Mindfulness

- Media and Digital Literacy as Forms of Individual Power

- (Mis)understanding of power in media texts

- Money and Power

- My synesthetic perception of "power"

- N >

- P >

- R >

- S >

- T >

- U >

- V >

- W >

- Completed pages

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- Author