- About

- Introduction

-

Browse the book

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- A >

- B >

- C >

- D >

- E >

- F >

- G >

- H >

- I >

- L >

-

M

>

- Main theories of power

- Making an effort is a prerequisite of using power

- Marxism and the meaning of power

- "May" power

- Meanings of power that are not directly related to social power

- Micropower: Individual power

- Mindfulness

- Media and Digital Literacy as Forms of Individual Power

- (Mis)understanding of power in media texts

- Money and Power

- My synesthetic perception of "power"

- N >

- P >

- R >

- S >

- T >

- U >

- V >

- W >

- Completed pages

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- Author

Did Louis XIV Have Absolute Power?

last updated: 2/27/2024 (completed pages might be rewritten over time)

I spent the first five years of my life in Peterhof, a satellite town of St. Petersburg, Russia. There, I lived with my parents in an apartment that my grandfather had received for his military service (he was a World War II veteran). Peterhof was originally created by Peter the Great, the same tsar who strategically founded the city of St. Petersburg in 1703 as the first port to connect Russia with the West. As part of his plan to modernize the country, Peter the Great brought in many innovations from Europe. In particular, Peterhof remains a testimony of Peter's admiration for the French culture of his time.

This admiration was somewhat of a paradox. In his extensive account of the life and reign of Louis XIV, historian Philip Mansel mentions the area of my childhood this way: "Despite his personal taste for simplicity, in 1714–23 [Peter the Great] built a vast country palace called Peterhof outside St. Petersburg: it was partly inspired by Versailles, with a park and fountains designed by a pupil of Le Nôtre called J. B. le Blond, and a nearby villa named Marlia [inspired by Marly near Versailles]" (Chapter 24, my emphasis).

I spent the first five years of my life in Peterhof, a satellite town of St. Petersburg, Russia. There, I lived with my parents in an apartment that my grandfather had received for his military service (he was a World War II veteran). Peterhof was originally created by Peter the Great, the same tsar who strategically founded the city of St. Petersburg in 1703 as the first port to connect Russia with the West. As part of his plan to modernize the country, Peter the Great brought in many innovations from Europe. In particular, Peterhof remains a testimony of Peter's admiration for the French culture of his time.

This admiration was somewhat of a paradox. In his extensive account of the life and reign of Louis XIV, historian Philip Mansel mentions the area of my childhood this way: "Despite his personal taste for simplicity, in 1714–23 [Peter the Great] built a vast country palace called Peterhof outside St. Petersburg: it was partly inspired by Versailles, with a park and fountains designed by a pupil of Le Nôtre called J. B. le Blond, and a nearby villa named Marlia [inspired by Marly near Versailles]" (Chapter 24, my emphasis).

Image credit: Peterhof by Slava Korolev

I walked in the Peterhof park many times alone and with friends, admiring its scope and beauty. Little did I know that years later, living in a different country, I would decide to refer to Louis XIV's reign to explain my theory of power. Peterhof seems to be a perfect manifestation of his immense influence. Even Peter the Great, who did not like luxury, decided to imitate the French king's extravagant style! But was Louis's influence truly limitless? To answer this question, I read the detailed account of this controversial king's life published by Philip Mansel (2020). Relying on the authority of this reputable historian, below I will explain why Louis XIV's power was far from absolute.

To be clear, I am not inventing a wheel. The idea that absolute monarchs did not have absolute power is not new. This is how political science scholar Keith Dowding puts it

in his entry on absolutism in Encyclopedia of Power:

"These monarchs had great formal powers, which in practice extended to closing down other power centers, emasculating parliaments, creating powerful bureaucracies and standing armies, and generally centralizing power to a greater extent than previously happened... [However, their power] can be overemphasized. Certainly there were other centers of power, notably the churches and nobility, though absolutist monarchs attempted to enfeeble the latter by requiring them to work with state officials on their lands. [I]t is not clear that the absolute rulers had significantly greater power than other rulers. Absolute rulers still needed to negotiate with barons and with the church and were beholden to powerful figures within their palaces and bureaucracies."

Still, the idea that absolute monarchs did not have absolute power might catch many people by surprise. In this essay, I draw on Mansel's account of Louis XIV's reign to bring some life to the dry language of the encyclopedia entry quoted above.

I must clarify that any historic account can only be a work of interpretation. Therefore, the description that I offer below can be contested by people who choose to interpret historical sources and accounts differently. My interpretation is guided by my personal belief in the importance of empathy. As a scholar, I want to support my theory of power, which claims that in any person's actions power always coexists with powerlessness (although this combination can take many forms depending on the person and their circumstances).

I acknowledge that it is my choice not to see Louis XIV merely as a haughty and heartless lover of exquisite entertainments. Instead, I choose to see him as a person who, like all of us, was born into the world of meanings and relationships that he did not fully comprehend. He tried to navigate this world the best could, in the process making many mistakes and hurting numerous people, which he was able to do due to the meanings of absolute monarchy instilled in his mind and reinforced by those around him.

I walked in the Peterhof park many times alone and with friends, admiring its scope and beauty. Little did I know that years later, living in a different country, I would decide to refer to Louis XIV's reign to explain my theory of power. Peterhof seems to be a perfect manifestation of his immense influence. Even Peter the Great, who did not like luxury, decided to imitate the French king's extravagant style! But was Louis's influence truly limitless? To answer this question, I read the detailed account of this controversial king's life published by Philip Mansel (2020). Relying on the authority of this reputable historian, below I will explain why Louis XIV's power was far from absolute.

To be clear, I am not inventing a wheel. The idea that absolute monarchs did not have absolute power is not new. This is how political science scholar Keith Dowding puts it

in his entry on absolutism in Encyclopedia of Power:

"These monarchs had great formal powers, which in practice extended to closing down other power centers, emasculating parliaments, creating powerful bureaucracies and standing armies, and generally centralizing power to a greater extent than previously happened... [However, their power] can be overemphasized. Certainly there were other centers of power, notably the churches and nobility, though absolutist monarchs attempted to enfeeble the latter by requiring them to work with state officials on their lands. [I]t is not clear that the absolute rulers had significantly greater power than other rulers. Absolute rulers still needed to negotiate with barons and with the church and were beholden to powerful figures within their palaces and bureaucracies."

Still, the idea that absolute monarchs did not have absolute power might catch many people by surprise. In this essay, I draw on Mansel's account of Louis XIV's reign to bring some life to the dry language of the encyclopedia entry quoted above.

I must clarify that any historic account can only be a work of interpretation. Therefore, the description that I offer below can be contested by people who choose to interpret historical sources and accounts differently. My interpretation is guided by my personal belief in the importance of empathy. As a scholar, I want to support my theory of power, which claims that in any person's actions power always coexists with powerlessness (although this combination can take many forms depending on the person and their circumstances).

I acknowledge that it is my choice not to see Louis XIV merely as a haughty and heartless lover of exquisite entertainments. Instead, I choose to see him as a person who, like all of us, was born into the world of meanings and relationships that he did not fully comprehend. He tried to navigate this world the best could, in the process making many mistakes and hurting numerous people, which he was able to do due to the meanings of absolute monarchy instilled in his mind and reinforced by those around him.

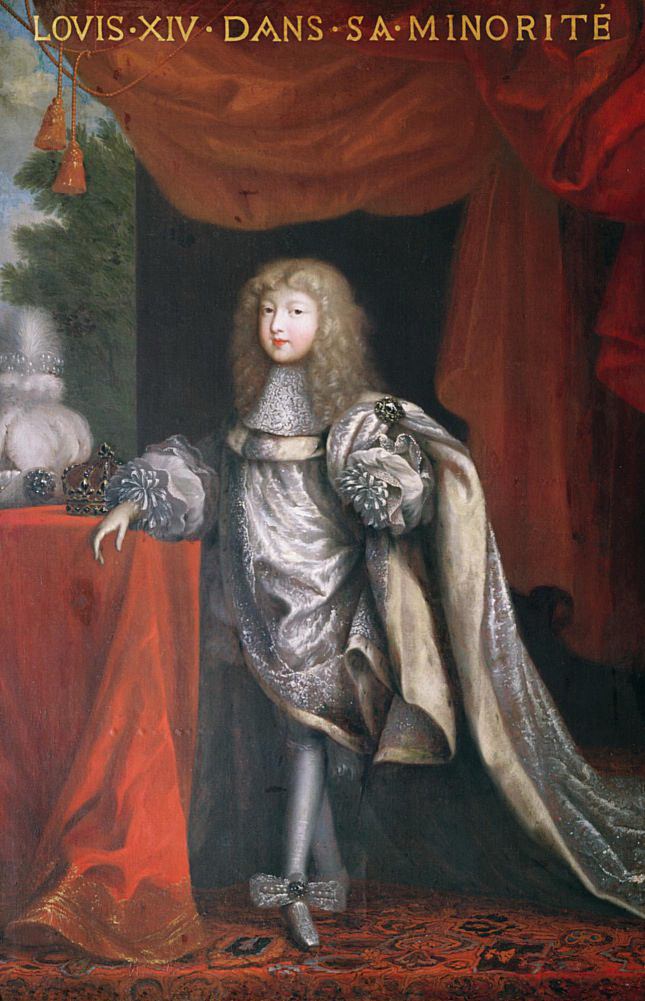

King's Childhood

When his father died in 1643, four-year-old Louis XIV was proclaimed King. Of course, he did not start managing France right away. Upon the death of her husband, Queen Anne became the regent, ruling with the help of Cardinal Mazarin until Louis reached the age of majority (13 years old) in 1651. After that, although his mother was not a regent anymore, the young King did not fully take state matters in his hands for another ten years, until Mazarin passed away in 1661.

Image credit: Louis XIV during his minority, c. 1643, by Pierre Mignard

Let us first take a look at the formative years of the future self-proclaimed Sun King.

We could hardly claim that Louis XIV came anywhere close to absolute power as a child.

But as King by law, perhaps he enjoyed a life of exceptional happiness and freedom?

Chapter I of Mansel's volume dispels this myth starting from the first sentence: "Even by royal standards, the family into which the future Louis XIV was born on 5 September 1638 was a nest of vipers." In this family (not atypical for a royal household of the time), closest relatives often could not trust or even stand each other. Intrigues flourished and rebellions were common. Queen Anne herself, being of Spanish origin, conspired against her husband (Louis XIII) and helped her home country during the conflict between Spain and France that was ongoing at the time.

Driving this point home, Mansel writes in the Introduction: "Thus antiquity, heredity, coronation and the widely proclaimed belief that the kings of France were representatives and images of God himself did not protect them from rebellion or assassination. France was a monarchy on a knife-edge... Both Henri IV’s son Louis XIII and his grandson Louis XIV would be threatened by repeated revolts and haunted by fears of new religious wars and acts of regicide."

All in all, Louis XIV's family could hardly be called a healthy environment for a young child trying to make sense of the world. Consider that, as Mansel argues, "[e]ven at the age of two, Louis was a pawn in his parents’ marriage. His feelings and manners were used as political weapons" (Chapter 1). The French court where this family was embedded was no better. "[A]t the French court every nuance of human relationships, and every inch of the royal apartments, could have political consequences. The court was a zone of negotiation, and a school of psychology, as well as a battlefield" (Chapter 1). Louis XIV had to navigate this battlefield, or rather minefield, of a court from a very young age while attending a variety of required events. As he was growing, his public life was quickly turning into "an unending sequence of ceremonies" (Chapter 2), which he soon came to detest but could not avoid.

One can only wonder how becoming a king at the age of four can affect a child. No psychological studies that would help us better understand what it really means to grow us as an absolute monarch can ever be conducted. But it is clear that, before Louis XIV could start exercising his power as a king, he received many lessons in powerlessness.

On the positive side, he had a close and tender relationship with his mother, something that few (if any) contemporary kings could boast. Unlike many royal parents of the epoch, Queen Anne spent a lot of time with her beloved first-born son and played an active role in his education.

In particular, she worked hard to instill in Louis the belief in the divine rights of the King of France. Queen Anne, who had experienced her own share of powerlessness, wanted absolute power for her son, probably because she believed that power could protect him and make him happy (these wishes are natural for any caring mother). We can assume that her lessons sank deep and determined how Louis XIV wanted to see himself and to be seen by others. Over the years, the conviction in his divine rights coupled with life's stresses, heartbreaks, and very human biases led Louis XIV to commit mistakes that hurt numerous people. One of these heartbreaks was his mother's painful death at the age of 64 (Louis himself was only 28 at the time) of breast cancer in a Parisian convent, where she had retired after her regency was over. Louis XIV was so shaken by her death that he barely visited the city since then, preferring to enhance his beloved Versailles and surrounding smaller residences.

Let us first take a look at the formative years of the future self-proclaimed Sun King.

We could hardly claim that Louis XIV came anywhere close to absolute power as a child.

But as King by law, perhaps he enjoyed a life of exceptional happiness and freedom?

Chapter I of Mansel's volume dispels this myth starting from the first sentence: "Even by royal standards, the family into which the future Louis XIV was born on 5 September 1638 was a nest of vipers." In this family (not atypical for a royal household of the time), closest relatives often could not trust or even stand each other. Intrigues flourished and rebellions were common. Queen Anne herself, being of Spanish origin, conspired against her husband (Louis XIII) and helped her home country during the conflict between Spain and France that was ongoing at the time.

Driving this point home, Mansel writes in the Introduction: "Thus antiquity, heredity, coronation and the widely proclaimed belief that the kings of France were representatives and images of God himself did not protect them from rebellion or assassination. France was a monarchy on a knife-edge... Both Henri IV’s son Louis XIII and his grandson Louis XIV would be threatened by repeated revolts and haunted by fears of new religious wars and acts of regicide."

All in all, Louis XIV's family could hardly be called a healthy environment for a young child trying to make sense of the world. Consider that, as Mansel argues, "[e]ven at the age of two, Louis was a pawn in his parents’ marriage. His feelings and manners were used as political weapons" (Chapter 1). The French court where this family was embedded was no better. "[A]t the French court every nuance of human relationships, and every inch of the royal apartments, could have political consequences. The court was a zone of negotiation, and a school of psychology, as well as a battlefield" (Chapter 1). Louis XIV had to navigate this battlefield, or rather minefield, of a court from a very young age while attending a variety of required events. As he was growing, his public life was quickly turning into "an unending sequence of ceremonies" (Chapter 2), which he soon came to detest but could not avoid.

One can only wonder how becoming a king at the age of four can affect a child. No psychological studies that would help us better understand what it really means to grow us as an absolute monarch can ever be conducted. But it is clear that, before Louis XIV could start exercising his power as a king, he received many lessons in powerlessness.

On the positive side, he had a close and tender relationship with his mother, something that few (if any) contemporary kings could boast. Unlike many royal parents of the epoch, Queen Anne spent a lot of time with her beloved first-born son and played an active role in his education.

In particular, she worked hard to instill in Louis the belief in the divine rights of the King of France. Queen Anne, who had experienced her own share of powerlessness, wanted absolute power for her son, probably because she believed that power could protect him and make him happy (these wishes are natural for any caring mother). We can assume that her lessons sank deep and determined how Louis XIV wanted to see himself and to be seen by others. Over the years, the conviction in his divine rights coupled with life's stresses, heartbreaks, and very human biases led Louis XIV to commit mistakes that hurt numerous people. One of these heartbreaks was his mother's painful death at the age of 64 (Louis himself was only 28 at the time) of breast cancer in a Parisian convent, where she had retired after her regency was over. Louis XIV was so shaken by her death that he barely visited the city since then, preferring to enhance his beloved Versailles and surrounding smaller residences.

Image credit: Queen Anne, Louis XIV's mother, c. 1620, by Peter Paul Rubens

There is another reason why Louis XIV hated Paris, and this reason further illustrates why his childhood was far from carefree. Mansel describes France's capital as "a cauldron of combustible institutions, at once the support and rival of the monarchy" (Chapter 2). Indeed, support and rivalry were often tied so close that this combination could easily become confusing, frustrating, and scary. The King would be glorified when riding through the street of Paris one day, but booed and threatened on another occasion. He was alternatively treated as god and as the worst person on the Earth. For instance, "On 18 May 1643, three days after his state entry into Paris, Louis proceeded from the Louvre through the streets caked in mud and excrement, for which Paris would remain notorious until the mid-nineteenth century, to the Parlement on the Île de la Cité" (Chapter 2, my emphasis).

Before Louis XIV reached the age of majority, Paris became a hotbed of dissent known as the Fronde. It was essentially a civil war. The Fronde was not a bottom-up rebellion; instead, it was led by aristocracy dissatisfied with their rights and privileges. The noblemen exploited popular discontent among Parisians who were not happy about growing taxes and diminishing authority of the Parlement. Notably, when Louis XIV was 12, an angry mob broke into the capital's palace and demanded to see the King.

Upon seeing the boy sleeping in his room, the rioters left the palace. Soon thereafter, the Queen and her son fled Paris accompanied by the court. On another occasion, Louis XIV and his mother were held in the same palace under virtual arrest.

This is not to say that Parisians did not have reasons to be concerned about the actions of the government trying to centralize its authority (something that absolutist monarchies were known for). Without excusing the French government's actions, my goal is to have my readers wonder how confusing messages and events of the time could affect the King's maturing mind. (And remember that, at that point, he was not the one making decisions about how France was supposed to be ruled.) We can assume that the idea of the King's divine rights was attractive for the growing Louis XIV as it promised certainty in a life full of conflicts and contradictions. In addition, the idea of the King's absolute power matched what Louis XIV often observed, since "[f]or most Frenchmen in the reigns of Louis XIII and Louis XIV, Christianity and monarchy were similar cults of hierarchy and obedience" (Chapter 1). Any rebellions and riots (even as extensive ones as the Fronde) could be written off as unpleasant aberrations. Inspired by his beloved mother, Louis XIV was growing up with the conviction that he was destined to become the King of the World. He was learning about his rights and responsibilities. But nobody could explain to him how the power he had been given was going to change him over time.

There is another reason why Louis XIV hated Paris, and this reason further illustrates why his childhood was far from carefree. Mansel describes France's capital as "a cauldron of combustible institutions, at once the support and rival of the monarchy" (Chapter 2). Indeed, support and rivalry were often tied so close that this combination could easily become confusing, frustrating, and scary. The King would be glorified when riding through the street of Paris one day, but booed and threatened on another occasion. He was alternatively treated as god and as the worst person on the Earth. For instance, "On 18 May 1643, three days after his state entry into Paris, Louis proceeded from the Louvre through the streets caked in mud and excrement, for which Paris would remain notorious until the mid-nineteenth century, to the Parlement on the Île de la Cité" (Chapter 2, my emphasis).

Before Louis XIV reached the age of majority, Paris became a hotbed of dissent known as the Fronde. It was essentially a civil war. The Fronde was not a bottom-up rebellion; instead, it was led by aristocracy dissatisfied with their rights and privileges. The noblemen exploited popular discontent among Parisians who were not happy about growing taxes and diminishing authority of the Parlement. Notably, when Louis XIV was 12, an angry mob broke into the capital's palace and demanded to see the King.

Upon seeing the boy sleeping in his room, the rioters left the palace. Soon thereafter, the Queen and her son fled Paris accompanied by the court. On another occasion, Louis XIV and his mother were held in the same palace under virtual arrest.

This is not to say that Parisians did not have reasons to be concerned about the actions of the government trying to centralize its authority (something that absolutist monarchies were known for). Without excusing the French government's actions, my goal is to have my readers wonder how confusing messages and events of the time could affect the King's maturing mind. (And remember that, at that point, he was not the one making decisions about how France was supposed to be ruled.) We can assume that the idea of the King's divine rights was attractive for the growing Louis XIV as it promised certainty in a life full of conflicts and contradictions. In addition, the idea of the King's absolute power matched what Louis XIV often observed, since "[f]or most Frenchmen in the reigns of Louis XIII and Louis XIV, Christianity and monarchy were similar cults of hierarchy and obedience" (Chapter 1). Any rebellions and riots (even as extensive ones as the Fronde) could be written off as unpleasant aberrations. Inspired by his beloved mother, Louis XIV was growing up with the conviction that he was destined to become the King of the World. He was learning about his rights and responsibilities. But nobody could explain to him how the power he had been given was going to change him over time.

Closer to Power

Between the year 1651 (when the King started formally ruling by himself, without the regent, at the age of 13) and the year 1661 (when Mazarin died), Louis XIV was gradually learning to manage his country. However, over this ten-year-long period, his decisions were often not his own, shaped by Mazarin's and his mother's wills. In an interesting twist of events, Mazarin and Queen Anne were rumored to have got secretly married; so the Cardinal, the former Regent, and the King formed a kind of nuclear family. Their relationships, just as any relationships between children and parents, were not free from tensions, but this bond was surprisingly tender according to the royal family standards of the time. Indeed, Louis XIV trusted and admired both his mother and Mazarin, which does not mean that he was always happy with their choices.

Image credit: Cardinal Jules Mazarin, 1658, by Pierre Mignard

It became particularly clear who was calling the shots in this family when Louis XIV fell madly in love with Marie Mancini, Mazarin's charming niece. When he shared his intention to marry Marie with his mother and Mazarin, their response shattered his hopes. Mazarin might have toyed with the idea of becoming the King's official uncle-in-law, but Queen Anne was firmly against it. It would have messed up her plan to protect her son from life's uncertainties by ensuring that he had absolute power as the King, which required strengthening political and dynastic bonds. Louis XIV was to marry Queen Anne's own niece, daughter of Philip IV of Spain.

Trying to persuade the pleading King to give up the politically inconvenient relationship, Mazarin composed a letter that serves as an example of contradictory messages that the young Louis was receiving about his power: "[Mazarin] reminded the King that he was not an individual but an institution: ‘Although you are the master in a certain sense to do what you wish, nevertheless you owe an account to God of your actions for your salvation and to the world for the maintenance of your glory and your reputation’" (Chapter 4). Although he was heartbroken, Louis XVI had to do what was considered his duty. Fulfilling his mother's will, in 1660 he married his double first cousin Maria Theresa of Spain.

As a side note, it must be added that absolute (or any other) monarchs seldom had a privilege to marry for love. In fact, they had to obey rules of dynastic marriages that "could be biological, as well as personal and political, disasters. In order to maintain their prestige, European sovereigns almost always married cousins from within ‘the family of kings’, whose ties were so strong that they wore mourning for each other as relations even when they were at war. Yet the products of inbreeding are predisposed to illnesses, including madness and infertility" (Chapter 5). Most of the children born from the union between Maria Teresa and Louis died young; this might have been an adverse consequence of inbreeding, which produces less viable offspring. Louis XIV was emotionally attached to all of his children, and each death became a new heartbreak.

In 1661, the year after the royal marriage was celebrated, Mazarin passed away, which was a hard blow for the King. As Mazarin was receiving his last religious rites, "[t]he King was crying so much, he was asked to leave the bedroom" (Chapter 5). Having to say goodbye first to his love to Marie Mancini, and then to his beloved mentor the Cardinal, were possibly the first devastating experiences in Louis XIV's life. Many more were to come. Nevertheless, in his early twenties, his heart had not hardened yet as it did in the later years of his reign. In Mansel's words, "[b]etween the ages of fourteen and thirty, between the abjection of the Fronde and the intoxication of absolutism, he was affable, informal and Parisian" (Chapter 4).

Louis was now 23 years old, and he was finally able to take the reign in his hands.

"To the amazement of Louis’ family, court and ministers, the day Mazarin died the King had announced, ‘I am determined henceforth to govern my state by myself.’ He wanted no over-powerful minister or relation, not even his mother, challenging his control of the government" (Chapter 6). After all the lessons of powerlessness that Louis XIV had received in his life so far, and fueled by the conviction that absolute power was his destiny, the King was ready to take all the power he could get.

As probably any other person who has ever walked the face of the Earth, Louis XIV was full of contradictions. He wanted to use the power that, in his mind, he was supposed to have, but he was not planning on using it solely for selfish reasons. After all, he was told for the first twenty years of his life by people he respected and loved that his responsibility was to strengthen his country and the Bourbon dynasty. Louis XIV thought that he would be able to rule France the best way he could if we eliminated all the intermediaries, which was a logical assumption based on what he had experienced so far. From then on, he spent a considerable amount of time managing – even micro-managing – as many things in his state as he could, usually with the conviction that he was doing good. One of the biggest contradictions of Louis XIV's personality was that he honestly wanted to make France the strongest and most admired country, but he could delude himself into believing that this was his primary interest when in reality his actions were guided by vanity, anxieties, and biases.

Louis is known as a monarch who haughtily said, "I am the state." However, as Mansel notes, the fact of him stating that in a speech or in writing was not recorded by any contemporary observers. It appears that this famous quote is an invention. By the same token, the image of Louis XIV as an absolute monarch is often distorted by the prism of time and by other people's perceptions. This image is full of myths that can prevent us from seeing both power and powerlessness that characterized the life of this King.

It became particularly clear who was calling the shots in this family when Louis XIV fell madly in love with Marie Mancini, Mazarin's charming niece. When he shared his intention to marry Marie with his mother and Mazarin, their response shattered his hopes. Mazarin might have toyed with the idea of becoming the King's official uncle-in-law, but Queen Anne was firmly against it. It would have messed up her plan to protect her son from life's uncertainties by ensuring that he had absolute power as the King, which required strengthening political and dynastic bonds. Louis XIV was to marry Queen Anne's own niece, daughter of Philip IV of Spain.

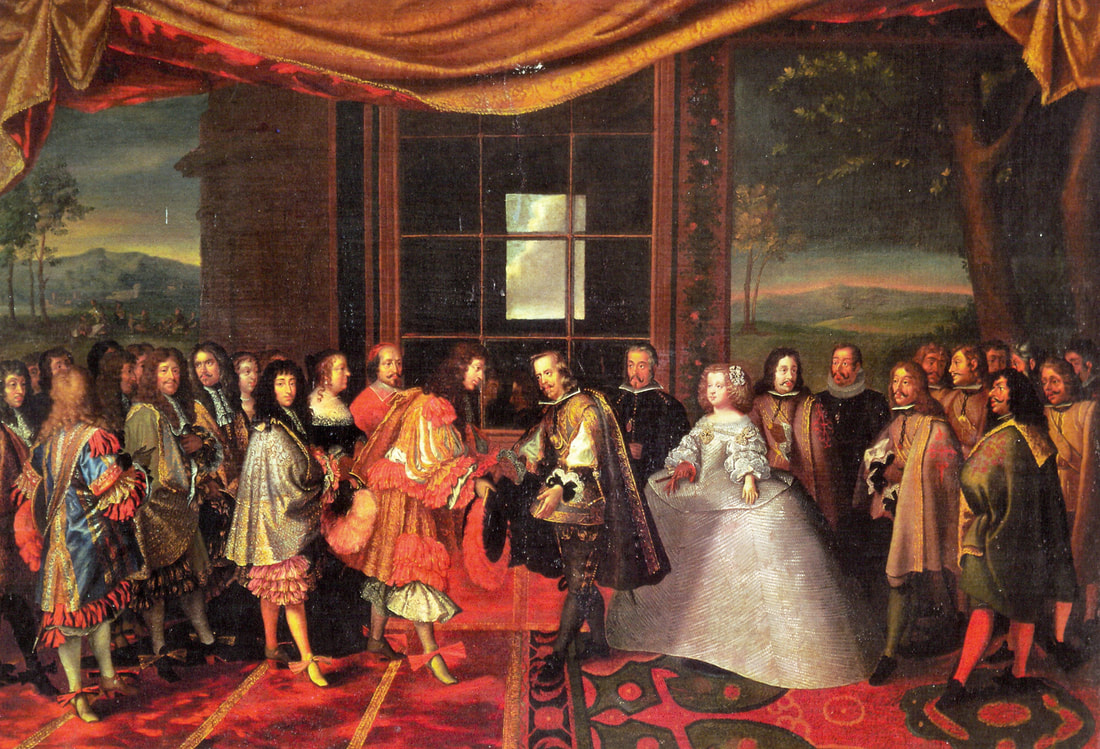

Trying to persuade the pleading King to give up the politically inconvenient relationship, Mazarin composed a letter that serves as an example of contradictory messages that the young Louis was receiving about his power: "[Mazarin] reminded the King that he was not an individual but an institution: ‘Although you are the master in a certain sense to do what you wish, nevertheless you owe an account to God of your actions for your salvation and to the world for the maintenance of your glory and your reputation’" (Chapter 4). Although he was heartbroken, Louis XVI had to do what was considered his duty. Fulfilling his mother's will, in 1660 he married his double first cousin Maria Theresa of Spain.

As a side note, it must be added that absolute (or any other) monarchs seldom had a privilege to marry for love. In fact, they had to obey rules of dynastic marriages that "could be biological, as well as personal and political, disasters. In order to maintain their prestige, European sovereigns almost always married cousins from within ‘the family of kings’, whose ties were so strong that they wore mourning for each other as relations even when they were at war. Yet the products of inbreeding are predisposed to illnesses, including madness and infertility" (Chapter 5). Most of the children born from the union between Maria Teresa and Louis died young; this might have been an adverse consequence of inbreeding, which produces less viable offspring. Louis XIV was emotionally attached to all of his children, and each death became a new heartbreak.

In 1661, the year after the royal marriage was celebrated, Mazarin passed away, which was a hard blow for the King. As Mazarin was receiving his last religious rites, "[t]he King was crying so much, he was asked to leave the bedroom" (Chapter 5). Having to say goodbye first to his love to Marie Mancini, and then to his beloved mentor the Cardinal, were possibly the first devastating experiences in Louis XIV's life. Many more were to come. Nevertheless, in his early twenties, his heart had not hardened yet as it did in the later years of his reign. In Mansel's words, "[b]etween the ages of fourteen and thirty, between the abjection of the Fronde and the intoxication of absolutism, he was affable, informal and Parisian" (Chapter 4).

Louis was now 23 years old, and he was finally able to take the reign in his hands.

"To the amazement of Louis’ family, court and ministers, the day Mazarin died the King had announced, ‘I am determined henceforth to govern my state by myself.’ He wanted no over-powerful minister or relation, not even his mother, challenging his control of the government" (Chapter 6). After all the lessons of powerlessness that Louis XIV had received in his life so far, and fueled by the conviction that absolute power was his destiny, the King was ready to take all the power he could get.

As probably any other person who has ever walked the face of the Earth, Louis XIV was full of contradictions. He wanted to use the power that, in his mind, he was supposed to have, but he was not planning on using it solely for selfish reasons. After all, he was told for the first twenty years of his life by people he respected and loved that his responsibility was to strengthen his country and the Bourbon dynasty. Louis XIV thought that he would be able to rule France the best way he could if we eliminated all the intermediaries, which was a logical assumption based on what he had experienced so far. From then on, he spent a considerable amount of time managing – even micro-managing – as many things in his state as he could, usually with the conviction that he was doing good. One of the biggest contradictions of Louis XIV's personality was that he honestly wanted to make France the strongest and most admired country, but he could delude himself into believing that this was his primary interest when in reality his actions were guided by vanity, anxieties, and biases.

Louis is known as a monarch who haughtily said, "I am the state." However, as Mansel notes, the fact of him stating that in a speech or in writing was not recorded by any contemporary observers. It appears that this famous quote is an invention. By the same token, the image of Louis XIV as an absolute monarch is often distorted by the prism of time and by other people's perceptions. This image is full of myths that can prevent us from seeing both power and powerlessness that characterized the life of this King.

Image credit: Louis XIV, c. 1655, by Charles Le Brun

Powerful/less King

Louis XIV clearly did not have absolute power as a child-king. He also did not have absolute power as a young man when Mazarin was still alive. How about the King's reign starting from the age of 23, when he began managing France as best as (he thought) he could? From then on and till the end of his life, Louis XIV's decisions influenced – and hurt – numerous people inside and outside of France. But it would be wrong to argue that he could do whatever he wanted, even as seemingly one of the most powerful monarchs in Europe of the time. It would be also wrong to argue that his life was always easy or fun, although the luxurious beauty of his court and the extravagant entertainments of Versailles suggested otherwise. Far from justifying all the mistakes that Louis XIV made during his eventful life, we can acknowledge how he tried to be a good person and to do what his thought (or wanted to think) was good for his country and people. We can also recognize how some of the King's mistakes stemmed from factors that were hard for him to fully comprehend or change, or how his delusions of grandeur coupled with anxieties about losing his power were shaped by his life's contradictions. I present details about various aspects of Louis's life and reign in the sections below.

1. King and his court

In order to understand the relationship between Louis XIV and his court, we first need to know that a court was an extended royal household. It could include thousands of individuals (many of them nobility) who lived close to the king and queen in order to serve them, but also to enjoy the power that came with this advantageous social position. When Versailles became Louis XIV's primary residence, his court, depending on the day, could consist of up to 10,000 people.

Having a large and beautiful court was considered essential for a king and queen to signal their power to the world. However, maintaining such a court was very expensive. Louis XIV poured a lot of money into first building and then improving Versailles because a royal residence needed to provide enough space for all the courtiers. Despite the strict etiquette that those had to obey, they were no slaves. In fact, they were there often not just to serve the royal family but also (and sometimes mostly) to achieve their own political and personal goals. Courts could be filled with intrigues and tensions, which sometimes created toxic environments that monarchs had to navigate on a daily basis. To Louis XIV's credit, "[he] made his family and court into an emotional community – unlike the venomous courts of the Stuarts, the Hanovers, the Romanovs and his own father, which were split by conspiracies and executions" (Chapter 14).

Both Louis XIV and his courtiers had to take part in numerous ceremonies that were not invented by any of them but inherited from previous reigns. Over time, Louis XIV introduced some innovations that made his court less formal. "[I]t was, as foreigners frequently remarked, more accessible, and less hierarchical, than other courts. Louis XIV himself disliked ceremonies and would write, in a famous phrase, ‘if there is a singularity in this monarchy, it is the free and easy access of subjects to the monarch'" (Chapter 13). Less formality meant less structure. "The Italian Primi Visconti described Louis XIV’s court as ‘a real confusion of men and women’. Another visitor from Italy... wrote in 1698: ‘when you want, you can see, talk with and almost touch the King.’ The King needed his cane not only for support, but to bar uninvited guests, or to fight to make room for the Queen and her ladies, or even for himself... Not even Louis XIV, for all the fear and awe he inspired, was in total control" (Chapter 13).

The strange combination of ceremoniousness and lack of formality characterized two essential daily rites – King's awakening ("lever") and going to bed ("coucher"). "Sometimes there were as many as a hundred men at the lever [admitted to the room after the King was dressed]... In contrast to their respectful silence in his youth, courtiers continued talking even when the King was praying by his bed. John Locke was surprised in December 1678 ‘by the noise and buzz of the rest of the chamber which is full of people standing and talking to one another’ (Chapter 13). In the process of getting ready for the day, the King would listen to the visitors and occasionally announce a piece of news. Both lever and coucher lasted for about an hour and a half. There were fewer people when the King was retiring to bed. After most of the visitors left, the part called petit [small] coucher began, when "wearing no more than his dressing gown, the King sat on his commode [toilet]. Even during his most basic functions, the King received one or two courtiers ‘by ceremony far more than by necessity’. They were proud recipients of the brevet d’affaires [chamber pot]... an honour which gave special opportunities to talk freely to the King and on occasion to ask for favours" (Chapter 13). It was not uncommon for kings and queens of the past to experience lack of privacy. On some occasions, like in the case of waking-up and going-to-bed ceremonies, Louis XIV even chose to increase this lack because he wanted to be as informal and accessible as the royal etiquette (and the need for some order) allowed.

As much as Louis XIV wanted to be in control, he would not have possibly been able to supervise everything in his country, not even in his court, himself. The King had to delegate responsibilities, so he wanted (but could not always guarantee) that they were assigned the best way possible. Not surprisingly, "[t]he King regarded job allocation as one of his principal duties" (Chapter 13). Serving this purpose "Versailles functioned as a national job centre, rather than as a gilded cage, for the nobility" (Chapter 13). Louis XIV's way to show his power was to avoid or delay job-related decisions, but this was also a way for him to make sure that jobs were given to people who deserved them. Courtiers depended on his decisions; on the downside for this King, this dependance meant that Louis XIV was constantly pestered by people who wanted something from him. For example, "[d]uring the King’s daily procession, through the Grande Galerie and the state apartment, to mass in the royal chapel, people presented petitions for jobs, pensions or promotion. The 103 placets [petitions] presented to the King at Versailles on 12 June 1702, carefully listed and summarized by an official, confirm his role as the engine in a vast machine distributing jobs and money" (Chapter 13).

Same as French people in general, courtiers could alternatively (or simultaneously) be in awe of the King and afraid of him, love him and question his actions. "Louis was aware that he was constantly criticized… Even in July 1672, at the height of Louis XIV’s success, courtiers criticized his ministers, his generals and his policies. By the end of the reign Madame de Maintenon was complaining that ‘freedom of speech in our court has been taken to excess.’ She too, however, criticized the King’s wars and entertainments in letters to friends" (Chapter 13). The King sometimes ignored these criticisms and sometimes listened to them. On a number of occasions, he welcomed in his court people who openly disagreed with him.

In fact, "the court, bringing so many intelligent and ambitious people together under one roof, fostered opposition as well as loyalty. La Fontaine and La Bruyère, for example, lived partly at court but criticized it in their writings. Saint-Simon used his years at Versailles to gather stories and information for memoirs extremely hostile to Louis XIV" (Chapter 13). Despite all this hostility, Saint-Simon also had many good things to say about the King. For example, this famous memoirist wrote about Louis XIV's charm, his "incomparable grace and majesty", about his kind-heartedness and politeness to everybody who surrounded him in court. "‘Never did anyone give with better grace, thereby augmenting the price of his favours,’ wrote Saint-Simon. [The King's] manners were more than skin deep. ‘Never was a man so naturally polite,’ Saint-Simon added: he raised his hat to every woman he met, even to the maids at Marly" (Chapter 14). According to Mansel's interpretation, based on a variety of historical sources, "Louis XIV’s warmth, charm and joie de vivre... strengthened the forces of power, fear, loyalty and ambition on which the monarchy normally relied" (Chapter 14).

1. King and his court

In order to understand the relationship between Louis XIV and his court, we first need to know that a court was an extended royal household. It could include thousands of individuals (many of them nobility) who lived close to the king and queen in order to serve them, but also to enjoy the power that came with this advantageous social position. When Versailles became Louis XIV's primary residence, his court, depending on the day, could consist of up to 10,000 people.

Having a large and beautiful court was considered essential for a king and queen to signal their power to the world. However, maintaining such a court was very expensive. Louis XIV poured a lot of money into first building and then improving Versailles because a royal residence needed to provide enough space for all the courtiers. Despite the strict etiquette that those had to obey, they were no slaves. In fact, they were there often not just to serve the royal family but also (and sometimes mostly) to achieve their own political and personal goals. Courts could be filled with intrigues and tensions, which sometimes created toxic environments that monarchs had to navigate on a daily basis. To Louis XIV's credit, "[he] made his family and court into an emotional community – unlike the venomous courts of the Stuarts, the Hanovers, the Romanovs and his own father, which were split by conspiracies and executions" (Chapter 14).

Both Louis XIV and his courtiers had to take part in numerous ceremonies that were not invented by any of them but inherited from previous reigns. Over time, Louis XIV introduced some innovations that made his court less formal. "[I]t was, as foreigners frequently remarked, more accessible, and less hierarchical, than other courts. Louis XIV himself disliked ceremonies and would write, in a famous phrase, ‘if there is a singularity in this monarchy, it is the free and easy access of subjects to the monarch'" (Chapter 13). Less formality meant less structure. "The Italian Primi Visconti described Louis XIV’s court as ‘a real confusion of men and women’. Another visitor from Italy... wrote in 1698: ‘when you want, you can see, talk with and almost touch the King.’ The King needed his cane not only for support, but to bar uninvited guests, or to fight to make room for the Queen and her ladies, or even for himself... Not even Louis XIV, for all the fear and awe he inspired, was in total control" (Chapter 13).

The strange combination of ceremoniousness and lack of formality characterized two essential daily rites – King's awakening ("lever") and going to bed ("coucher"). "Sometimes there were as many as a hundred men at the lever [admitted to the room after the King was dressed]... In contrast to their respectful silence in his youth, courtiers continued talking even when the King was praying by his bed. John Locke was surprised in December 1678 ‘by the noise and buzz of the rest of the chamber which is full of people standing and talking to one another’ (Chapter 13). In the process of getting ready for the day, the King would listen to the visitors and occasionally announce a piece of news. Both lever and coucher lasted for about an hour and a half. There were fewer people when the King was retiring to bed. After most of the visitors left, the part called petit [small] coucher began, when "wearing no more than his dressing gown, the King sat on his commode [toilet]. Even during his most basic functions, the King received one or two courtiers ‘by ceremony far more than by necessity’. They were proud recipients of the brevet d’affaires [chamber pot]... an honour which gave special opportunities to talk freely to the King and on occasion to ask for favours" (Chapter 13). It was not uncommon for kings and queens of the past to experience lack of privacy. On some occasions, like in the case of waking-up and going-to-bed ceremonies, Louis XIV even chose to increase this lack because he wanted to be as informal and accessible as the royal etiquette (and the need for some order) allowed.

As much as Louis XIV wanted to be in control, he would not have possibly been able to supervise everything in his country, not even in his court, himself. The King had to delegate responsibilities, so he wanted (but could not always guarantee) that they were assigned the best way possible. Not surprisingly, "[t]he King regarded job allocation as one of his principal duties" (Chapter 13). Serving this purpose "Versailles functioned as a national job centre, rather than as a gilded cage, for the nobility" (Chapter 13). Louis XIV's way to show his power was to avoid or delay job-related decisions, but this was also a way for him to make sure that jobs were given to people who deserved them. Courtiers depended on his decisions; on the downside for this King, this dependance meant that Louis XIV was constantly pestered by people who wanted something from him. For example, "[d]uring the King’s daily procession, through the Grande Galerie and the state apartment, to mass in the royal chapel, people presented petitions for jobs, pensions or promotion. The 103 placets [petitions] presented to the King at Versailles on 12 June 1702, carefully listed and summarized by an official, confirm his role as the engine in a vast machine distributing jobs and money" (Chapter 13).

Same as French people in general, courtiers could alternatively (or simultaneously) be in awe of the King and afraid of him, love him and question his actions. "Louis was aware that he was constantly criticized… Even in July 1672, at the height of Louis XIV’s success, courtiers criticized his ministers, his generals and his policies. By the end of the reign Madame de Maintenon was complaining that ‘freedom of speech in our court has been taken to excess.’ She too, however, criticized the King’s wars and entertainments in letters to friends" (Chapter 13). The King sometimes ignored these criticisms and sometimes listened to them. On a number of occasions, he welcomed in his court people who openly disagreed with him.

In fact, "the court, bringing so many intelligent and ambitious people together under one roof, fostered opposition as well as loyalty. La Fontaine and La Bruyère, for example, lived partly at court but criticized it in their writings. Saint-Simon used his years at Versailles to gather stories and information for memoirs extremely hostile to Louis XIV" (Chapter 13). Despite all this hostility, Saint-Simon also had many good things to say about the King. For example, this famous memoirist wrote about Louis XIV's charm, his "incomparable grace and majesty", about his kind-heartedness and politeness to everybody who surrounded him in court. "‘Never did anyone give with better grace, thereby augmenting the price of his favours,’ wrote Saint-Simon. [The King's] manners were more than skin deep. ‘Never was a man so naturally polite,’ Saint-Simon added: he raised his hat to every woman he met, even to the maids at Marly" (Chapter 14). According to Mansel's interpretation, based on a variety of historical sources, "Louis XIV’s warmth, charm and joie de vivre... strengthened the forces of power, fear, loyalty and ambition on which the monarchy normally relied" (Chapter 14).

Image credit: Louis XIV meets his Spanish bride Maria Teresa on the Island of Pheasants in 1660, a later copy painted by Jacques Laumosnier

2. Hardworking king

It is easy to picture Louis XIV spending most of his time at extravagant parties. These parties, indeed, happened, and they were as lavish as one can imagine. However, they only took a fraction of the King's time. When Louis XIV was not resting or having fun, he could be found diligently working for what he believed to be the good of France. "‘Work is the first object of His Majesty and he prefers it to everything else,’ wrote [the First Minister] Colbert. Colbert was right. Until the end of the reign the King almost never missed a council meeting, every morning from 9 to 11 from Monday to Friday, and held lengthy meetings about finances three times a week in the evening. In addition he worked alone with the secretaries of state: Lionne on Saturday and Sunday; Colbert... on Wednesday and Thursday; Le Tellier, for war, on Tuesday. He also held council meetings in the evening before supper at 10. The King’s hours were said to be as regular as a monk’s" (Chapter 7).

"Louis XIV spent as much time with his ministers as with his family, his court officials or his mistresses" (Chapter 14). It helped that the King was by nature very energetic. "Louis XIV’s enjoyment of his court was heightened by his stupendous vitality. He could work six or seven hours a day, or more, in addition to performing the daily rituals of the lever, mass, public dinner and coucher, and following a strenuous outdoor routine of hunts, shoots and walks" (Chapter 14). Of course, Louis XIV's dedication can be explained by his intention to govern the country by himself, which he expressed in his early twenties. This dedication can be also explained by the fear that, if he had let other people take too much responsibility, he would not have been in control. There was certainly an element of vanity, as Louis XIV wanted to take responsibility as well as credit. But there was also sincere commitment and curiosity, as the King strived to understand different aspects of France and its relationships with other countries by himself, rather than rely on knowledge of intermediaries.

Whether he was indeed able to govern the way he wanted, remains an open question.

"Despite the King’s hard work, and his access to information from non-ministerial sources, many believed that... he could be ‘absolutely governed by his ministers’. Absolutism could be a façade hiding the power of ministers and factions to persuade the King to take the decisions they wanted. He could be their instrument not their master" (Chapter 14). The truth might be hiding somewhere in-between these two extreme views. Louis XIV was probably not absolutely governed by his ministers, but he also did not have absolute power over them.

Louis's addiction to micro-management continued during war time. "On 14 March 1691 Dangeau wrote: ‘the King is never for one moment not working.’ He inspected French trenches around the city for six hours at a time and worked on political affairs in the evening" (Chapter 18). When not on campaign, the King spent hours trying to understand and control what was going on in the field. For example, when war minister Louvois passed away and Louvois's son Barbezieux was appointed to take his place, Louis was happy to take most responsibility for all the war-related decisions in his hands. He "worked with Barbezieux many hours most days, dictating letters for the minister to write in his own name, or writing letters in his own hand. Louis also wrote hundreds of letters about the war to princes, generals, army intendants, directly through his own secretaries, rather than through the Secretary of State for War. Many thought the King had become his own war minister. He drew up plans of campaign, and selected and promoted officers himself" (Chapter 18).

The value of this and other instances of war-related micro-management have been questioned by Louis XIV's contemporaries as well as by historians. "Louis’ critics... said that, as supreme warlord, he hampered generals’ actions in the field by micro-management from his office at Versailles" (Chapter 18). They pointed out that the King's hard work was not always selfless, but rather a way to prove to himself and others that he was in control. For example, after France's victory in one siege, memoirist "Le Peletier... wrote that the siege had been undertaken by Louis XIV for emotional rather than military reasons, to flatter himself: ‘to show all Europe that without the help of [the War Minister] M. de Louvois His Majesty on his own could execute a great design’. Indeed Louis’ own account confirms Le Peletier. He wrote that he was ‘all the more satisfied by his conquest because this great expedition was entirely his own work... he had undertaken it [guided] solely by his own judgement; executed it, so to say, with his own hands’" (Chapter 18).

Although the King's working style was initially well-intentioned, as time went by, this approach created more problems than it solved. In fact, Mansel believes that "[t]he King’s methods of government, and delusions about French power, would contribute to the disasters of the second half of his reign" (Chapter 14). Louis XIV did not learn from his early mistakes. During subsequent wars, "[e]ven more than before, generals were paralysed by micro-management from Versailles. Working late into the night, the King sent frequent couriers to his generals, with demands for the smallest details of news, and counsels of prudence, as is clear from many letters in his hasty, sprawling handwriting" (Chapter 20).

While Louis XIV was not just a partying king, and despite the fact that he worked hard (partially) because he wanted to bring glory to France and its people, the King's actions weakened his country. Ruling France the way he wanted, understanding motivations behind his own decisions, or fully grasping their outcomes was outside of Louis XIV's power. Beyond his vanity and the sincere commitment to the good of France, the King's attempts to micro-manage everything, from wars to the construction of Versailles, reveal his anxieties, his fear of not being in control.

3. King's image

Louis XIV considered maintaining the political and cultural status of France as his essential responsibility. One might note that to achieve this goal, the King conveniently needed to maintain his own status, which let him justify enormous expenses related to food, clothes, and residence, as well as to such entertainments as balls, hunting, and theater. After working hard for several hours and taking part in ceremonies that he did not enjoy, the King could relax at a party while telling himself that its extravagance was required for showing the glory of France to people inside and outside of the country. "His parties, like Versailles itself, were... intended to impress ‘all our subjects in general’ and Europe. The Gazette de France wrote that the [these beautiful entertainments] showed that Louis XIV was the first monarch in the world. Louis wrote in his memoirs – pretending that parties were organized only for the good of his country, rather than also for his pleasure – that such [parties] made ‘a very advantageous impression’, on foreigners as well as Frenchmen, ‘of magnificence, of power, of wealth and grandeur’" (Chapter 13).

Indeed, the impression was powerful. France of the time was a major cultural center in almost everything related to fashion and art. French court's dresses were copied by monarchs and nobility around Europe. French styles were popular among elites even in countries that were at war with France. Although Louis XIV most certainly derived a lot of pleasure from sending these messages of wealth and fashion to the world, maintaining the image of cultural power was not easy, as it required constant work and a lot of money (and money, as we will see in one of the sections below, was an issue).

2. Hardworking king

It is easy to picture Louis XIV spending most of his time at extravagant parties. These parties, indeed, happened, and they were as lavish as one can imagine. However, they only took a fraction of the King's time. When Louis XIV was not resting or having fun, he could be found diligently working for what he believed to be the good of France. "‘Work is the first object of His Majesty and he prefers it to everything else,’ wrote [the First Minister] Colbert. Colbert was right. Until the end of the reign the King almost never missed a council meeting, every morning from 9 to 11 from Monday to Friday, and held lengthy meetings about finances three times a week in the evening. In addition he worked alone with the secretaries of state: Lionne on Saturday and Sunday; Colbert... on Wednesday and Thursday; Le Tellier, for war, on Tuesday. He also held council meetings in the evening before supper at 10. The King’s hours were said to be as regular as a monk’s" (Chapter 7).

"Louis XIV spent as much time with his ministers as with his family, his court officials or his mistresses" (Chapter 14). It helped that the King was by nature very energetic. "Louis XIV’s enjoyment of his court was heightened by his stupendous vitality. He could work six or seven hours a day, or more, in addition to performing the daily rituals of the lever, mass, public dinner and coucher, and following a strenuous outdoor routine of hunts, shoots and walks" (Chapter 14). Of course, Louis XIV's dedication can be explained by his intention to govern the country by himself, which he expressed in his early twenties. This dedication can be also explained by the fear that, if he had let other people take too much responsibility, he would not have been in control. There was certainly an element of vanity, as Louis XIV wanted to take responsibility as well as credit. But there was also sincere commitment and curiosity, as the King strived to understand different aspects of France and its relationships with other countries by himself, rather than rely on knowledge of intermediaries.

Whether he was indeed able to govern the way he wanted, remains an open question.

"Despite the King’s hard work, and his access to information from non-ministerial sources, many believed that... he could be ‘absolutely governed by his ministers’. Absolutism could be a façade hiding the power of ministers and factions to persuade the King to take the decisions they wanted. He could be their instrument not their master" (Chapter 14). The truth might be hiding somewhere in-between these two extreme views. Louis XIV was probably not absolutely governed by his ministers, but he also did not have absolute power over them.

Louis's addiction to micro-management continued during war time. "On 14 March 1691 Dangeau wrote: ‘the King is never for one moment not working.’ He inspected French trenches around the city for six hours at a time and worked on political affairs in the evening" (Chapter 18). When not on campaign, the King spent hours trying to understand and control what was going on in the field. For example, when war minister Louvois passed away and Louvois's son Barbezieux was appointed to take his place, Louis was happy to take most responsibility for all the war-related decisions in his hands. He "worked with Barbezieux many hours most days, dictating letters for the minister to write in his own name, or writing letters in his own hand. Louis also wrote hundreds of letters about the war to princes, generals, army intendants, directly through his own secretaries, rather than through the Secretary of State for War. Many thought the King had become his own war minister. He drew up plans of campaign, and selected and promoted officers himself" (Chapter 18).

The value of this and other instances of war-related micro-management have been questioned by Louis XIV's contemporaries as well as by historians. "Louis’ critics... said that, as supreme warlord, he hampered generals’ actions in the field by micro-management from his office at Versailles" (Chapter 18). They pointed out that the King's hard work was not always selfless, but rather a way to prove to himself and others that he was in control. For example, after France's victory in one siege, memoirist "Le Peletier... wrote that the siege had been undertaken by Louis XIV for emotional rather than military reasons, to flatter himself: ‘to show all Europe that without the help of [the War Minister] M. de Louvois His Majesty on his own could execute a great design’. Indeed Louis’ own account confirms Le Peletier. He wrote that he was ‘all the more satisfied by his conquest because this great expedition was entirely his own work... he had undertaken it [guided] solely by his own judgement; executed it, so to say, with his own hands’" (Chapter 18).

Although the King's working style was initially well-intentioned, as time went by, this approach created more problems than it solved. In fact, Mansel believes that "[t]he King’s methods of government, and delusions about French power, would contribute to the disasters of the second half of his reign" (Chapter 14). Louis XIV did not learn from his early mistakes. During subsequent wars, "[e]ven more than before, generals were paralysed by micro-management from Versailles. Working late into the night, the King sent frequent couriers to his generals, with demands for the smallest details of news, and counsels of prudence, as is clear from many letters in his hasty, sprawling handwriting" (Chapter 20).

While Louis XIV was not just a partying king, and despite the fact that he worked hard (partially) because he wanted to bring glory to France and its people, the King's actions weakened his country. Ruling France the way he wanted, understanding motivations behind his own decisions, or fully grasping their outcomes was outside of Louis XIV's power. Beyond his vanity and the sincere commitment to the good of France, the King's attempts to micro-manage everything, from wars to the construction of Versailles, reveal his anxieties, his fear of not being in control.

3. King's image

Louis XIV considered maintaining the political and cultural status of France as his essential responsibility. One might note that to achieve this goal, the King conveniently needed to maintain his own status, which let him justify enormous expenses related to food, clothes, and residence, as well as to such entertainments as balls, hunting, and theater. After working hard for several hours and taking part in ceremonies that he did not enjoy, the King could relax at a party while telling himself that its extravagance was required for showing the glory of France to people inside and outside of the country. "His parties, like Versailles itself, were... intended to impress ‘all our subjects in general’ and Europe. The Gazette de France wrote that the [these beautiful entertainments] showed that Louis XIV was the first monarch in the world. Louis wrote in his memoirs – pretending that parties were organized only for the good of his country, rather than also for his pleasure – that such [parties] made ‘a very advantageous impression’, on foreigners as well as Frenchmen, ‘of magnificence, of power, of wealth and grandeur’" (Chapter 13).

Indeed, the impression was powerful. France of the time was a major cultural center in almost everything related to fashion and art. French court's dresses were copied by monarchs and nobility around Europe. French styles were popular among elites even in countries that were at war with France. Although Louis XIV most certainly derived a lot of pleasure from sending these messages of wealth and fashion to the world, maintaining the image of cultural power was not easy, as it required constant work and a lot of money (and money, as we will see in one of the sections below, was an issue).

Image credit: Versailles by Armand Khoury

Finding a justification in the need to uphold France's status, Louis XIV extended his micro-management to everything related to Versailles. There, he "was not merely following fashion or building what he thought a king of France should build. Unlike other monarchs, he decided every aspect of the plan and decoration, and often visited the building site" (Chapter 8). Unlike Parisian attitudes and many other things in France that Louis XIV could not fully control, Versailles as a physical space was where the King felt that he was in charge. As a result of all the work and money put into it, Versailles inevitably left foreign ambassadors and other travelers deeply impressed. But it would be wrong to assume that these outsiders were the only audience allowed to marvel at France's grandeur embodied in the King's majestic residence. Any ordinary French men and women were welcome to visit as well. Thus, apart from the grandeur, accessibility was another aspect of the King's image that he diligently cultivated. (Of course, one might also point out that such accessibility was also useful to assert Louis's power inside France.)

"The public was usually allowed into the gardens and palace of Versailles ‘without distinction of sex, age or condition’. Only the dirty or diseased were stopped by the Gardes du Corps at the entrances. Sometimes, however, the King preferred to be alone when giving orders to the gardeners. The garden was also closed if the King felt ‘overwhelmed’ by the multitude of people, ‘above all from Paris’; ‘la canaille’ [scoundrels], [as one memoirist wrote] damaged the statues and vases. However, Louis XIV’s sense of kingship trumped his love of privacy: the public was always allowed back. Without the public, the gardens would have lost their purpose. In 1704 the King ordered fences to be removed from the bosquets [regular gardens] of Versailles so that the public could enjoy walking inside them (which it cannot now do, except on the few days the fountains are playing). Versailles was built for Europe, as well as for France" (Chapter 12). In another instance of micro-management, Louis XIV wrote his own guidebook titled The Way to Show the Gardens of Versailles, and he subsequently rewrote it six times.

This accessibility extended beyond Versailles. "The public could also wander in and out of the courtyards of the Louvre and its apartments, even in the evening after dinner. As [the King's mother] was dying, for example, Paris workmen came to her guard room in the Louvre to learn the news. A visiting Italian called Sébastien Locatelli (whose description is confirmed by other contemporaries) wrote in 1665: ‘the King wants all his subjects to enter freely so that he can be informed if necessary of very important events like rebellions, treasons and threats of revolt’... Louis XIV’s collections of sculpture and paintings in the Louvre, his furniture in the Garde-meuble, the royal library and the Gobelins factory could be visited by members of the public, if they were well dressed. Thus the court of France inspired and financed creativity, gave artists space in which to work and displayed the results to the public" (Chapter 8).

While we can see how the accessibility cultivated by Louis XIV was meant to contribute to his power, it was not possible without certain sacrifices that marked his powerlessness. Accessibility could sometimes encourage disrespect that the King could not or did not want to do anything about. When during some festivities the public was invited to the gardens of Versailles, the crowd could be hard to control. For example, during a festivity to celebrate the end of a war, "[m]ost ambassadors left early... after they had been jostled by hordes of unruly guests, as they often were at the French court. The Gardes du Corps could not or would not control them. The Queen herself had to wait half an hour before she could enter the theatre, while the King had to ask gentlemen to leave, to ensure that she and other ladies were given seats" (Chapter 13). On another occasion, "[i]n the scramble for supper after the ball, Monsieur [Louis's brother] was knocked to the ground and trampled on. The King too was jostled, and had to use his cane to make space for the ladies. However, the Venetian Ambassador was impressed. ‘At that hour when the glory and grandeur of France were made manifest, one can see how poor, how despicable are the imitations of other nations’" (Chapter 18).

Louis XIV also wanted to be seen as a modern king. Despite his dislike of France's capital city, he spent considerable resources modernizing it, to Parisians' benefit. He "made Paris one of Europe’s most modern cities... with the best shops and post service. Public carriages able to take up to eight passengers began on certain routes in 1662. The city walls were demolished after 1669 and turned into tree-lined boulevards. An English visitor in 1672 called Francis Tallents was impressed by the ‘wondrous clean and handsome’ streets, the ‘great and excellent order’ and the lack of beggars... In 1667 Louis XIV also introduced public lighting to Paris – the first city in Europe to have it, before Amsterdam and London. Lamps, hanging 15 feet above the street, from ropes attached to buildings on each side, made the city safer, encouraging Parisians to go out at night. There were 5,400 such lights by 1702. Louis XIV’s and [his First Minister] Colbert’s most original achievement was the expansion of the Louvre into the ‘palace of the arts’ which it remains to this day" (Chapter 8).

The King's preoccupation with his image certainly had a dark side. "On 19 October 1684 Louis XIV announced at the lever his plan to divert and canalize part of the River Eure, 40 miles to the west, in order to bring more water to the reservoirs and improve water pressure at Versailles… Some 1,500 soldiers died during the operations. More fell ill from the marshy air and bad water, and later spread diseases among other troops. Vauban, the voice of reason, was appalled, criticizing the King in a letter to Louvois on 29 June 1685 for trying to surpass the Romans while ruling only a tenth of their Empire: ‘the King will be accountable to all nations and to posterity.’ As with the construction of Versailles on a bad site, the difficulty of the enterprise was part of its attraction. Louis XIV wanted to demonstrate omnipotence" (Chapter 12). In the following years, many more people would be sacrificed to the Sun King's pursuit of glory and immortality.

The King worked so hard to control his image that he failed to notice how, for lack of better words, his image was controlling him. The fact that many see Louis XIV as a monarch who had absolute power is a result not only of the King's efforts but also of other people's assumptions about him. These assumptions were often expressed through flattery, which royal subjects used not only because they were afraid of the King but also because they wanted something from him. Louis XIV was happy to hear himself described as a monarch with absolute power because these words suggested that he had achieved what, according to his mother, was rightfully his. As a person who, on many occasions, was not in complete control of what was going on in his country, in his court, and even in his personal life, embracing the image of the absolutely powerful King was highly attractive for Louis XIV. He craved flattery so much that over the years this became a sort of addiction that gradually changed his personality and allowed him to justify many cruel decisions in the second half of his reign.

"By 1680, in his own eyes, Louis XIV was master of France and arbiter of Europe. Colbert wrote that year, exaggerating government control, ‘everything reflects total submission . . . the authority of the Parlement reduced to a point where only the shadow of it remains.’ Even ‘the misery and distress of the peoples’ served royal power, since the King could control ‘this proud and inconstant nation with the restraint of extreme necessity’... Versailles was considered the wonder of the world. Royal academies glorified the King, the monarchy and France. Louis XIV had won almost universal admiration as administrator, commander, patron and king. Yet his achievements hid inner weaknesses. As a young man Louis had been considered kind and ‘civil and courteous beyond anything one can imagine’. By the age of forty, blinded by flattery, power, success, a new man had emerged... Narcissism, tactlessness, lack of realism and failure to foresee consequences had become characteristics of Louis XIV" (Chapter 14).

The King was a celebrity of the time, and celebrities are often overwhelmed by attention and misunderstood by people who claim to know them. Royal subjects felt special when they were allowed in his presence. But when not close to the King, they could enjoy gossiping about him and picking apart his flaws. When he died, people cried but also rejoiced, ignoring his suffering. As it happens with celebrities, those who were in awe of the King did not really understand him as a person, with his concerns and joys, heartbreaks and worries. But they certainly expected a lot from him, and different people expected different things. For example, during wars that devastated France financially and made it one of the most hated countries in Europe, ordinary French men and women were understandably outraged by taxes, but many were also proud of their country's victories. Some even wanted the King to reject peace offers and keep fighting for the glory of the country.

King's subjects, as well as Louis XIV himself, were captives of the same illusions associated with absolute monarchy. Ironically, Louis often ignored how his actions aimed to maintain France's glory actually damaged its image. In particular, the wars he waged and his persecution of Protestants (to be discussed below) undermined the glory of France and turned him into the most unpopular monarch of the time.

Finding a justification in the need to uphold France's status, Louis XIV extended his micro-management to everything related to Versailles. There, he "was not merely following fashion or building what he thought a king of France should build. Unlike other monarchs, he decided every aspect of the plan and decoration, and often visited the building site" (Chapter 8). Unlike Parisian attitudes and many other things in France that Louis XIV could not fully control, Versailles as a physical space was where the King felt that he was in charge. As a result of all the work and money put into it, Versailles inevitably left foreign ambassadors and other travelers deeply impressed. But it would be wrong to assume that these outsiders were the only audience allowed to marvel at France's grandeur embodied in the King's majestic residence. Any ordinary French men and women were welcome to visit as well. Thus, apart from the grandeur, accessibility was another aspect of the King's image that he diligently cultivated. (Of course, one might also point out that such accessibility was also useful to assert Louis's power inside France.)

"The public was usually allowed into the gardens and palace of Versailles ‘without distinction of sex, age or condition’. Only the dirty or diseased were stopped by the Gardes du Corps at the entrances. Sometimes, however, the King preferred to be alone when giving orders to the gardeners. The garden was also closed if the King felt ‘overwhelmed’ by the multitude of people, ‘above all from Paris’; ‘la canaille’ [scoundrels], [as one memoirist wrote] damaged the statues and vases. However, Louis XIV’s sense of kingship trumped his love of privacy: the public was always allowed back. Without the public, the gardens would have lost their purpose. In 1704 the King ordered fences to be removed from the bosquets [regular gardens] of Versailles so that the public could enjoy walking inside them (which it cannot now do, except on the few days the fountains are playing). Versailles was built for Europe, as well as for France" (Chapter 12). In another instance of micro-management, Louis XIV wrote his own guidebook titled The Way to Show the Gardens of Versailles, and he subsequently rewrote it six times.