- About

- Introduction

-

Browse the book

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- A >

- B >

- C >

- D >

- E >

- F >

- G >

- H >

- I >

- L >

-

M

>

- Main theories of power

- Making an effort is a prerequisite of using power

- Marxism and the meaning of power

- "May" power

- Meanings of power that are not directly related to social power

- Micropower: Individual power

- Mindfulness

- Media and Digital Literacy as Forms of Individual Power

- (Mis)understanding of power in media texts

- Money and Power

- My synesthetic perception of "power"

- N >

- P >

- R >

- S >

- T >

- U >

- V >

- W >

- Completed pages

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- Author

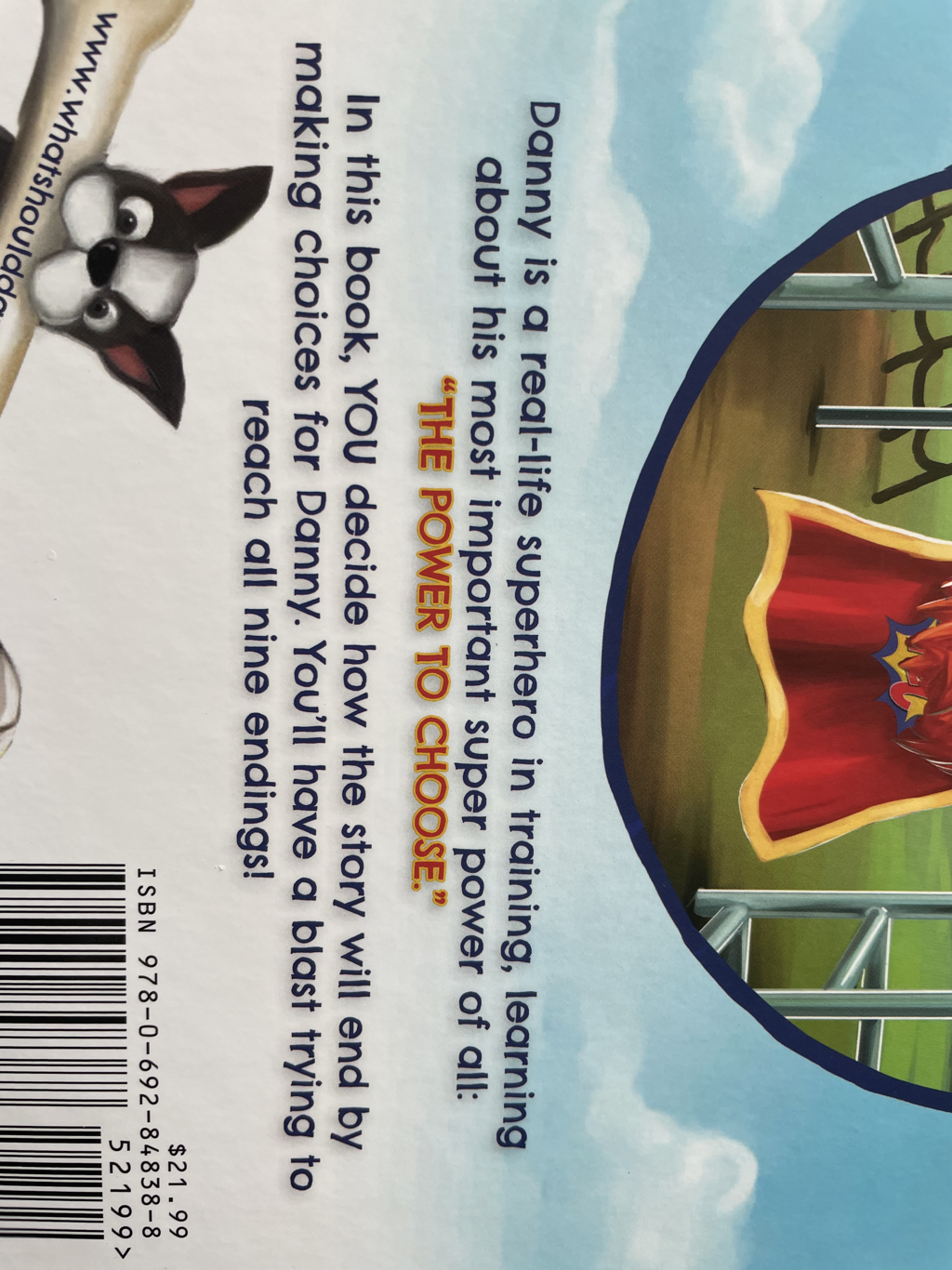

Choice

PAGE IN PROGRESS

What you see here is a page of my hypertext book POWER of meanings // MEANINGS of power. Initially empty, this page will slowly be filled with thoughts, notes, and quotes. One day, I will use them to write a coherent entry, similar to these completed pages. Thank you for your interest and patience!

What you see here is a page of my hypertext book POWER of meanings // MEANINGS of power. Initially empty, this page will slowly be filled with thoughts, notes, and quotes. One day, I will use them to write a coherent entry, similar to these completed pages. Thank you for your interest and patience!

From Ch 25 of history of archaeologuy:

The second example is South Africa, which, after the overthrow of apartheid in 1994, wanted to establish a fairer society; an essential part of this process was the creation of a new school curriculum in 1995, as stated by the republic’s Education Department:

"What is the purpose of history?

A study of history builds the capacity of people to make informed choices in order to contribute constructively to society and to advance democracy. History, as a vehicle of personal empowerment, engenders in learners an understanding of human agency, which brings with it the knowledge that, as human beings, they have choices, and that they can make the decision to change the world for the better. [my emphasis]

A rigorous process of historical enquiry:

• encourages and assists constructive debate through careful evaluation of a broad range of evidence and diverse points of view;

• provides a critical understanding of socio-economic systems in their historical perspective and their impact on people;

• supports the view that historical truth consists of a multiplicity of voices expressing varying and often contradictory versions of the same history."

(Education Department of the Republic of South Africa 2008, 7)

Making true choices is in itself a form of power. But what looking like making a choice is not necessarily a making-a-choice situation. Making true choices is form of mental power as it requires a mental effort.

We can choose from a range of options, but we do not choose the range of options that we need to choose from.

YOU DECIDE what happens next.

In any situation you decide how to react. To blame or to take responsibility. To give up or to go on. To raise your voice or to ask a question and listen.

choice is power

choice is power as influence because we make a decision about how things will be, it is about limited resources

Determinism - our choices do not matter as much

I believe that it is important to understand that we can make choices, but also to see limitations of our choices [give me wisdom to know what I can change, give me strength to change what I can change, give me patience to accept what I cannot change]

Making choices does not mean making free choices. We need to see what stands behind those choices. Sofie's choice is the famous example. She made the choice that she had to make. The choice that she really wanted to make was not offered to her as an option.

A person with a mental illness might seem to be making choices, but the mental illness affects their choices, so these choices are not free.

from Unwinding Anxiety:

“in fact, the OFC sets up a reward hierarchy so that you can make decisions efficiently without having to exert too much mental energy. This is especially true when you are making choices. Your OFC assigns each of your previously performed behaviors a value, and when given a choice—let’s say between two behaviors—it can then choose the more valuable one. This helps you make choice decisions quickly and easily without having to think too much about them.”

choose to see life as miserable or as an opportunity to learn and grow

” Our life itself, with all its unpredictability and factors that are beyond our control, is the training ground.”

https://www.tenpercent.com/meditationweeklyblog/the-warrior-and-the-caregiver

from Unwinding Anxiously- seeing your hardships as your teacher

Letting go of hate by questioning the very idea of evil: https://www.npr.org/2023/05/21/1176864308/religion-hate-evil-spirituality-simran-jeet-singh-sikh?utm_source=Klaviyo&utm_medium=campaign&_kx=uXKY7Y_39hYG3GPkxzgt8LldzLrnEO60BhP9Ij-Kj7c%3D.TAzfUF

"The very simple practice, the starting place, is to take 10 seconds each day and see the humanity in someone who is different from yourself. You can start in the easy places: family members, friends, colleagues, coworkers. But once you get through that list and you need to find someone else, you'll start seeing strangers you never noticed before. People you wouldn't otherwise connect with. And what I've found with this practice is that the strangeness starts to go away with these 10 seconds every day. It doesn't have to be super cheesy, you don't have to lock eyes and stare. Just notice someone and try to think about who they are and where they're coming from and just see their humanity."

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/compatibilism/

« A natural way to think of an agent’s control over her conduct at a moment in time is in terms of her ability to select among, or choose between, alternative courses of action. This picture of control stems from common features of our perspectives as practical deliberators settling on courses of action. If a person is choosing between voting for Clinton as opposed to Trump, it is plausible to assume that her freedom with regard to her voting consists, at least partially, in her ability to choose between these two alternatives. On this account, acting with free will requires alternative possibilities. A natural way to model this account of free will is in terms of an agent’s future as a garden of forking paths branching off from a single past. A locus of freely willed action arises when the present offers, from an agent’s (singular) past, more than one path into the future. On this model of human agency, then, when a person acts of her own free will, she could have acted otherwise. »

-muffin cone” episode of bluey - power / ability to choose behavior

The second example is South Africa, which, after the overthrow of apartheid in 1994, wanted to establish a fairer society; an essential part of this process was the creation of a new school curriculum in 1995, as stated by the republic’s Education Department:

"What is the purpose of history?

A study of history builds the capacity of people to make informed choices in order to contribute constructively to society and to advance democracy. History, as a vehicle of personal empowerment, engenders in learners an understanding of human agency, which brings with it the knowledge that, as human beings, they have choices, and that they can make the decision to change the world for the better. [my emphasis]

A rigorous process of historical enquiry:

• encourages and assists constructive debate through careful evaluation of a broad range of evidence and diverse points of view;

• provides a critical understanding of socio-economic systems in their historical perspective and their impact on people;

• supports the view that historical truth consists of a multiplicity of voices expressing varying and often contradictory versions of the same history."

(

Making true choices is in itself a form of power. But what looking like making a choice is not necessarily a making-a-choice situation. Making true choices is form of mental power as it requires a mental effort.

We can choose from a range of options, but we do not choose the range of options that we need to choose from.

YOU DECIDE what happens next.

In any situation you decide how to react. To blame or to take responsibility. To give up or to go on. To raise your voice or to ask a question and listen.

choice is power

choice is power as influence because we make a decision about how things will be, it is about limited resources

Determinism - our choices do not matter as much

I believe that it is important to understand that we can make choices, but also to see limitations of our choices [give me wisdom to know what I can change, give me strength to change what I can change, give me patience to accept what I cannot change]

Making choices does not mean making free choices. We need to see what stands behind those choices. Sofie's choice is the famous example. She made the choice that she had to make. The choice that she really wanted to make was not offered to her as an option.

A person with a mental illness might seem to be making choices, but the mental illness affects their choices, so these choices are not free.

from Unwinding Anxiety:

“in fact, the OFC sets up a reward hierarchy so that you can make decisions efficiently without having to exert too much mental energy. This is especially true when you are making choices. Your OFC assigns each of your previously performed behaviors a value, and when given a choice—let’s say between two behaviors—it can then choose the more valuable one. This helps you make choice decisions quickly and easily without having to think too much about them.”

choose to see life as miserable or as an opportunity to learn and grow

” Our life itself, with all its unpredictability and factors that are beyond our control, is the training ground.”

https://www.tenpercent.com/meditationweeklyblog/the-warrior-and-the-caregiver

from Unwinding Anxiously- seeing your hardships as your teacher

Letting go of hate by questioning the very idea of evil: https://www.npr.org/2023/05/21/1176864308/religion-hate-evil-spirituality-simran-jeet-singh-sikh?utm_source=Klaviyo&utm_medium=campaign&_kx=uXKY7Y_39hYG3GPkxzgt8LldzLrnEO60BhP9Ij-Kj7c%3D.TAzfUF

"The very simple practice, the starting place, is to take 10 seconds each day and see the humanity in someone who is different from yourself. You can start in the easy places: family members, friends, colleagues, coworkers. But once you get through that list and you need to find someone else, you'll start seeing strangers you never noticed before. People you wouldn't otherwise connect with. And what I've found with this practice is that the strangeness starts to go away with these 10 seconds every day. It doesn't have to be super cheesy, you don't have to lock eyes and stare. Just notice someone and try to think about who they are and where they're coming from and just see their humanity."

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/compatibilism/

« A natural way to think of an agent’s control over her conduct at a moment in time is in terms of her ability to select among, or choose between, alternative courses of action. This picture of control stems from common features of our perspectives as practical deliberators settling on courses of action. If a person is choosing between voting for Clinton as opposed to Trump, it is plausible to assume that her freedom with regard to her voting consists, at least partially, in her ability to choose between these two alternatives. On this account, acting with free will requires alternative possibilities. A natural way to model this account of free will is in terms of an agent’s future as a garden of forking paths branching off from a single past. A locus of freely willed action arises when the present offers, from an agent’s (singular) past, more than one path into the future. On this model of human agency, then, when a person acts of her own free will, she could have acted otherwise. »

-muffin cone” episode of bluey - power / ability to choose behavior

If you are interested in getting updates about this project (e.g., when new pages are published), please sign up for the newsletter on my main website.

THIS WEBSITE CONTAINS NO AI-GENERATED CONTENT

- About

- Introduction

-

Browse the book

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- A >

- B >

- C >

- D >

- E >

- F >

- G >

- H >

- I >

- L >

-

M

>

- Main theories of power

- Making an effort is a prerequisite of using power

- Marxism and the meaning of power

- "May" power

- Meanings of power that are not directly related to social power

- Micropower: Individual power

- Mindfulness

- Media and Digital Literacy as Forms of Individual Power

- (Mis)understanding of power in media texts

- Money and Power

- My synesthetic perception of "power"

- N >

- P >

- R >

- S >

- T >

- U >

- V >

- W >

- Completed pages

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- Author