- About

- Introduction

-

Browse the book

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- A >

- B >

- C >

- D >

- E >

- F >

- G >

- H >

- I >

- L >

-

M

>

- Main theories of power

- Making an effort is a prerequisite of using power

- Marxism and the meaning of power

- "May" power

- Meanings of power that are not directly related to social power

- Micropower: Individual power

- Mindfulness

- Media and Digital Literacy as Forms of Individual Power

- (Mis)understanding of power in media texts

- Money and Power

- My synesthetic perception of "power"

- N >

- P >

- R >

- S >

- T >

- U >

- V >

- W >

- Completed pages

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- Author

Michel Foucault: "Power Is Everywhere"

last updated: 10/18/2023 (completed pages might be rewritten over time)

I will not tell you to read books by Michel Foucault –unless you already tried and liked them. Not because I think that this postmodernist French philosopher is no good. On the contrary, in my opinion, his works contain precious clues for understanding people and their relationships. But, to be honest, Foucault's books are hard to get through for anybody without special preparation or inclination (or even with those!). That said, I am going to quote him below (sparingly) and explain why (I think) his ideas are so important.

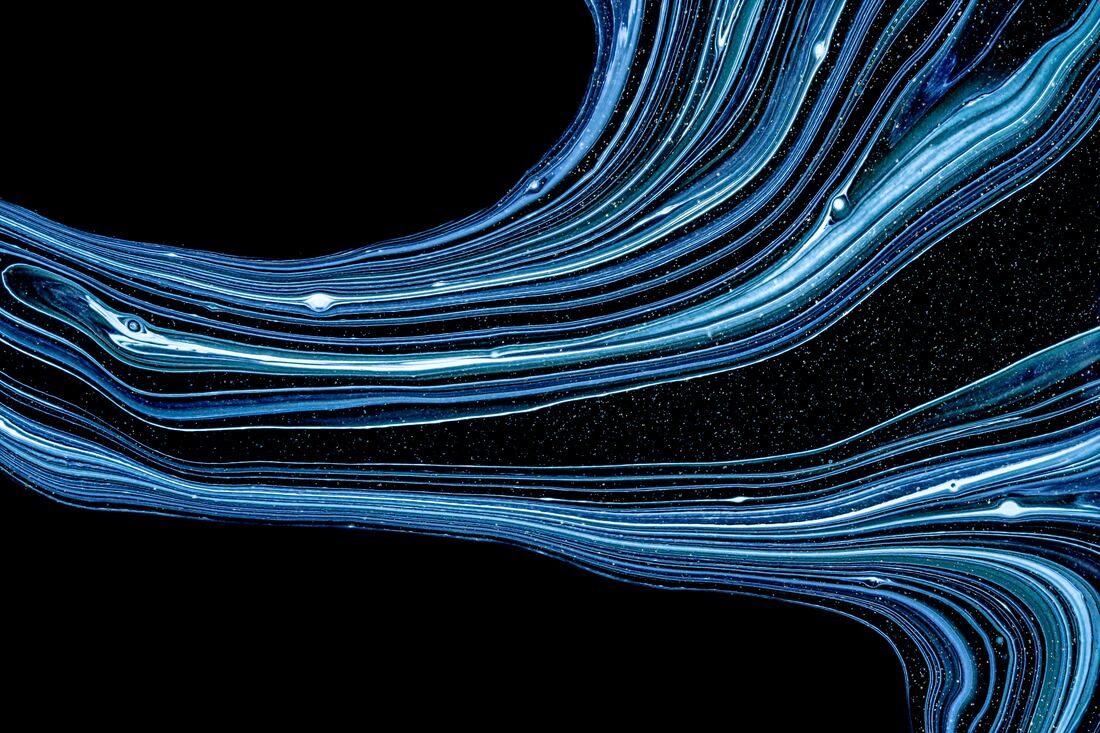

I first heard about Foucault back in Russia at St. Petersburg State University in the early 2000's. While my professors were raving about him and French postmodernist philosophers in general, I was frustrated and confused by this school of thought. Still, one of Foucault's ideas stood out and stuck with me, probably because it came with an intriguing mental image. Foucault, I was told, wrote a lot about power. Among other things, he wrote that power is like a flow that is constantly moving though society. It never solidifies, although it does sometimes concentrate in certain "nodes" of the social system. Foucault certainly did not deny that power inequalities and abuses exist, but he was also apparently saying that things are more complicated than they seem to be.

This image of fluid power was stored in my memory until I started writing my own book (about media). In that book, I attempted to explain my position as a paradox: On one hand, we need to acknowledge problems associated with media and work on fixing them. On the other hand, blaming certain individuals or groups for creating these problems will not bring us closer to any long-term solutions. This was, essentially, a conversation about power. We blame somebody when we think that they have power over the situation (they caused it or they do not want to change it). And I was trying to explain that blame is unhelpful because things are more complicated than they seem to be. It is not just us vs. them, we are all in this together. It was at that point that Foucault's ideas about fluid power came in handy.

I will not tell you to read books by Michel Foucault –unless you already tried and liked them. Not because I think that this postmodernist French philosopher is no good. On the contrary, in my opinion, his works contain precious clues for understanding people and their relationships. But, to be honest, Foucault's books are hard to get through for anybody without special preparation or inclination (or even with those!). That said, I am going to quote him below (sparingly) and explain why (I think) his ideas are so important.

I first heard about Foucault back in Russia at St. Petersburg State University in the early 2000's. While my professors were raving about him and French postmodernist philosophers in general, I was frustrated and confused by this school of thought. Still, one of Foucault's ideas stood out and stuck with me, probably because it came with an intriguing mental image. Foucault, I was told, wrote a lot about power. Among other things, he wrote that power is like a flow that is constantly moving though society. It never solidifies, although it does sometimes concentrate in certain "nodes" of the social system. Foucault certainly did not deny that power inequalities and abuses exist, but he was also apparently saying that things are more complicated than they seem to be.

This image of fluid power was stored in my memory until I started writing my own book (about media). In that book, I attempted to explain my position as a paradox: On one hand, we need to acknowledge problems associated with media and work on fixing them. On the other hand, blaming certain individuals or groups for creating these problems will not bring us closer to any long-term solutions. This was, essentially, a conversation about power. We blame somebody when we think that they have power over the situation (they caused it or they do not want to change it). And I was trying to explain that blame is unhelpful because things are more complicated than they seem to be. It is not just us vs. them, we are all in this together. It was at that point that Foucault's ideas about fluid power came in handy.

Image credit: Solen Feyissa

Foucault's book The History of Sexuality, Vol. I: The Will to Knowledge contains an oft-quoted phrase: "Power is everywhere... because it comes from everywhere.” What might this mean? To me, Foucault's most crucial contribution is that he challenged what I call binary thinking about power. In other words, he challenged the idea that power is simply what some people have and while others don't. Instead of seeing power as concentrated (centered) in certain social institutions or in some people's hands, Foucault suggested that power is de-centered, and that it does not belong to anybody in particular. He wrote that power is not a static system but rather a kind of ever-changing flow. At the same time, he did not say that power is equally distributed throughout society at any given moment.

Inspired by Foucault's ideas, in my book Media Is Us I included a chapter titled "Paradoxes of Power." I argued that we should certainly talk about injustices and do our best to correct them, but we should not hope to solve society's problems simply by dividing people into villains –who have power and abuse it– and victims –who lack power and suffer.

(In an interesting twist of events, Foucault's ideas about power have been used by some critical theory scholars in ways that have actually reinforced the binary thinking instead of further challenging it. This contradiction makes more sense if we consider Foucault's elaborate writing style, which opens possibilities for different –sometimes contradictory–interpretations of his work. Another reason might be that Foucault never proposed a coherent theory of power unifying different ideas about this major concept.)

So what exactly did Foucault say about power in The Will to Knowledge? (If you need to find an exact place in the book: Foucault's ideas about de-centered power are explained in Part 4, “The Deployment of Sexuality”, and even more specifically, in Section 2, titled "Method".) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy gives us the gist of Foucault's argument:

"We should not try to look for the center of power, or for the individuals, institutions or classes that rule, but should rather construct a 'microphysics of power' that focuses on the multitude of loci of power spread throughout a society: families, workplaces, everyday practices, and marginal institutions. One has to analyze power relations from the bottom up and not from the top down, and to study the myriad ways in which the subjects themselves are constituted in these diverse but intersecting networks. Although dispersed among various interlacing networks throughout society, power nevertheless has a rationality, a series of aims and objectives, and the means of attaining them. This does not imply that any individual has consciously formulated them."

Foucault's book The History of Sexuality, Vol. I: The Will to Knowledge contains an oft-quoted phrase: "Power is everywhere... because it comes from everywhere.” What might this mean? To me, Foucault's most crucial contribution is that he challenged what I call binary thinking about power. In other words, he challenged the idea that power is simply what some people have and while others don't. Instead of seeing power as concentrated (centered) in certain social institutions or in some people's hands, Foucault suggested that power is de-centered, and that it does not belong to anybody in particular. He wrote that power is not a static system but rather a kind of ever-changing flow. At the same time, he did not say that power is equally distributed throughout society at any given moment.

Inspired by Foucault's ideas, in my book Media Is Us I included a chapter titled "Paradoxes of Power." I argued that we should certainly talk about injustices and do our best to correct them, but we should not hope to solve society's problems simply by dividing people into villains –who have power and abuse it– and victims –who lack power and suffer.

(In an interesting twist of events, Foucault's ideas about power have been used by some critical theory scholars in ways that have actually reinforced the binary thinking instead of further challenging it. This contradiction makes more sense if we consider Foucault's elaborate writing style, which opens possibilities for different –sometimes contradictory–interpretations of his work. Another reason might be that Foucault never proposed a coherent theory of power unifying different ideas about this major concept.)

So what exactly did Foucault say about power in The Will to Knowledge? (If you need to find an exact place in the book: Foucault's ideas about de-centered power are explained in Part 4, “The Deployment of Sexuality”, and even more specifically, in Section 2, titled "Method".) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy gives us the gist of Foucault's argument:

"We should not try to look for the center of power, or for the individuals, institutions or classes that rule, but should rather construct a 'microphysics of power' that focuses on the multitude of loci of power spread throughout a society: families, workplaces, everyday practices, and marginal institutions. One has to analyze power relations from the bottom up and not from the top down, and to study the myriad ways in which the subjects themselves are constituted in these diverse but intersecting networks. Although dispersed among various interlacing networks throughout society, power nevertheless has a rationality, a series of aims and objectives, and the means of attaining them. This does not imply that any individual has consciously formulated them."

Image credit: arturo aguirre

The Will to Knowledge is a book about sexuality, a topic which Foucault was keenly interested in as a gay man. However, rather than citing Foucault's examples related to sexuality, I will talk about de-centered power by using a comparison of a king vs. his subject (for example, a peasant). I am especially interested in the way Foucault challenged the binary thinking about power –the idea that people are divided into those who have power and those who don't. I like the king vs. peasant comparison because it is one of the most extreme examples that come to mind when one thinks about power as a binary: the king is the powerful one, while the peasant is powerless.

The binary thinking about power goes like this: Those who have power (e.g., kings) use it to (a) keep this power and (b) make others (e.g., peasants) do things that those others often do not enjoy doing. So the king will write laws to make sure that, if peasants are unhappy, they will not come and take his crown away. This repressive power does certainly exist, according to Foucault, but that's not necessarily the kind of power that deserves most attention. There is only so much you can do by force.

Foucault suggested that we should analyze power relations not just from top down (how the king controls his subjects) but also from bottom up (e.g., how his subjects' actions make monarchy possible). Focusing on the repressive power used by the king (e.g., chop off the head of anybody who conspired against him) will help us get only half of the story. We should also explore how power grows from the bottom up –for example, how some peasants' sincere veneration of the king, despite all his laws and decisions that hurt them, supports the monarchy.

In other words, power is not only simply embodied in and wielded by the king. Paradoxically, power that the king uses is not entirely his to begin with. This power is made possible through actions of many other individuals, from the very bottom of society to its very top. In some ways, the king is not in control of his own power because he was born into his social position the same as the lowliest peasant was. The king is often a prisoner of society’s rules that he did not create, he does not fully understand, and that he does not even always benefit from (I will explore these ideas in more detail on the page about Louis XIV and Absolute Power).

Foucault suggests that top-down power coming from some specific center would not be able to use repression to achieve or maintain control. He specifically argues that there is no top-down duality in power. In other words, power is not something that spreads from the very top to the lowest and least powerful layers of the social system. In this sense, Foucault could say that it was Louis XIV's wishful thinking to imagine himself as Sun King (le Roi Soleil), with power emanating from his authority like light from the sun, moving to whose close to him and from them further and further away till the rays reached the deepest layers of society.

The Will to Knowledge is a book about sexuality, a topic which Foucault was keenly interested in as a gay man. However, rather than citing Foucault's examples related to sexuality, I will talk about de-centered power by using a comparison of a king vs. his subject (for example, a peasant). I am especially interested in the way Foucault challenged the binary thinking about power –the idea that people are divided into those who have power and those who don't. I like the king vs. peasant comparison because it is one of the most extreme examples that come to mind when one thinks about power as a binary: the king is the powerful one, while the peasant is powerless.

The binary thinking about power goes like this: Those who have power (e.g., kings) use it to (a) keep this power and (b) make others (e.g., peasants) do things that those others often do not enjoy doing. So the king will write laws to make sure that, if peasants are unhappy, they will not come and take his crown away. This repressive power does certainly exist, according to Foucault, but that's not necessarily the kind of power that deserves most attention. There is only so much you can do by force.

Foucault suggested that we should analyze power relations not just from top down (how the king controls his subjects) but also from bottom up (e.g., how his subjects' actions make monarchy possible). Focusing on the repressive power used by the king (e.g., chop off the head of anybody who conspired against him) will help us get only half of the story. We should also explore how power grows from the bottom up –for example, how some peasants' sincere veneration of the king, despite all his laws and decisions that hurt them, supports the monarchy.

In other words, power is not only simply embodied in and wielded by the king. Paradoxically, power that the king uses is not entirely his to begin with. This power is made possible through actions of many other individuals, from the very bottom of society to its very top. In some ways, the king is not in control of his own power because he was born into his social position the same as the lowliest peasant was. The king is often a prisoner of society’s rules that he did not create, he does not fully understand, and that he does not even always benefit from (I will explore these ideas in more detail on the page about Louis XIV and Absolute Power).

Foucault suggests that top-down power coming from some specific center would not be able to use repression to achieve or maintain control. He specifically argues that there is no top-down duality in power. In other words, power is not something that spreads from the very top to the lowest and least powerful layers of the social system. In this sense, Foucault could say that it was Louis XIV's wishful thinking to imagine himself as Sun King (le Roi Soleil), with power emanating from his authority like light from the sun, moving to whose close to him and from them further and further away till the rays reached the deepest layers of society.

Image credit: Jonathan Borba

According to Foucault, rather than being repressive and centered, power exists through an interplay of various social forces. This interplay is changing from moment to moment in each relationship and is, therefore, unstable. Here is what the oft-quoted phrase by Foucault looks in context: “[Power] is produced from one moment to the next, at every point, or rather in every relation from one point to another. Power is everywhere, not because it embraces everything, but because it comes from everywhere.” A few lines later he continues: “Power is not something that is acquired, seized or shared, something that one holds on to or allows to slip away. Power is exercised from innumerable points in the interplay of non egalitarian and mobile relations.”

According to Foucault, power is not about external control or prohibition. Power should not be imagined only as a king punishing his subjects for their transgressions. Power is productive, it creates rather than simply negates and limits. In this sense, everyday actions of the king’s subjects make the monarchy possible the same as (or perhaps even more than) the punishment of those subjects who dare to question the king’s authority.

Foucault challenges the binary thinking about power quite literally by saying: “Power comes from below. That is, there is no binary and all-encompassing opposition between rulers and ruled at the root of power relations.” This does not mean that the king's subjects do not suffer from his laws and decisions, or that the king does not enjoy his authority. It would be wrong to interpret Foucault's ideas as suggesting that, because there is no binary opposition in power, there are also no inequalities. But the root of these inequalities is not in the power as binary, so they cannot be resolved if we only focus on the binary opposition of the powerful vs. the powerless ones.

The crux of the paradox laid out by Foucault can be difficult to make sense of. He wrote: “Power relations are both intentional and non subjective.” This can be interpreted as Foucault saying that people –both kings and their subjects– are not some kind of automatons: they do have plans and they make decisions. However, paradoxically, their choices are not always entirely theirs. Power is "non subjective" in the sense that nobody is entirely in control of the situation even if it seems that they have quite a bit of power to change things. (This is related to paradoxes of free will that I introduce on a different page.)

According to Foucault, rather than being repressive and centered, power exists through an interplay of various social forces. This interplay is changing from moment to moment in each relationship and is, therefore, unstable. Here is what the oft-quoted phrase by Foucault looks in context: “[Power] is produced from one moment to the next, at every point, or rather in every relation from one point to another. Power is everywhere, not because it embraces everything, but because it comes from everywhere.” A few lines later he continues: “Power is not something that is acquired, seized or shared, something that one holds on to or allows to slip away. Power is exercised from innumerable points in the interplay of non egalitarian and mobile relations.”

According to Foucault, power is not about external control or prohibition. Power should not be imagined only as a king punishing his subjects for their transgressions. Power is productive, it creates rather than simply negates and limits. In this sense, everyday actions of the king’s subjects make the monarchy possible the same as (or perhaps even more than) the punishment of those subjects who dare to question the king’s authority.

Foucault challenges the binary thinking about power quite literally by saying: “Power comes from below. That is, there is no binary and all-encompassing opposition between rulers and ruled at the root of power relations.” This does not mean that the king's subjects do not suffer from his laws and decisions, or that the king does not enjoy his authority. It would be wrong to interpret Foucault's ideas as suggesting that, because there is no binary opposition in power, there are also no inequalities. But the root of these inequalities is not in the power as binary, so they cannot be resolved if we only focus on the binary opposition of the powerful vs. the powerless ones.

The crux of the paradox laid out by Foucault can be difficult to make sense of. He wrote: “Power relations are both intentional and non subjective.” This can be interpreted as Foucault saying that people –both kings and their subjects– are not some kind of automatons: they do have plans and they make decisions. However, paradoxically, their choices are not always entirely theirs. Power is "non subjective" in the sense that nobody is entirely in control of the situation even if it seems that they have quite a bit of power to change things. (This is related to paradoxes of free will that I introduce on a different page.)

Image credit: Pixabay

The following passage appears to support this interpretation (emphasis mine): "There is no power that is exercised without a series of aims and objectives. But this does not mean that it results from the choice or decision of an individual subject. Let us not look for the headquarters that presides over its rationality. Neither the caste which governs, nor the groups which control the state apparatus, nor those who make the most important economic decisions direct the entire network of power that functions in a society and makes it function. The rationality of power is characterized by tactics that are often quite explicit at the restricted level where they are inscribed... tactics which, becoming connected to one another, attracting and propagating one another but finding their base of support and their condition elsewhere end by forming comprehensive systems. The logic is perfectly clear, the aims decipherable. And yet it is often the case that no one is there to have invented them and few who can be said to have formulated them."

Foucault's interpretation of power raises several important questions. If no individual is completely responsible for how society functions, why is society the way it is? If nobody is fully in control, can anybody be held accountable for some individuals' discomfort or sufferings? We wouldn't blame people for their own misfortunes, would we? If nobody is in control, how can we hope to change things? Can we change things?? These are some of the questions that I attempt to answer with my own theory of power.

SOURCES:

Foucault, M. (2012/1976). The history of sexuality: An introduction. (Trans. by R. Hurley).

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (last updated August 5, 2022). Michel Foucault.

The following passage appears to support this interpretation (emphasis mine): "There is no power that is exercised without a series of aims and objectives. But this does not mean that it results from the choice or decision of an individual subject. Let us not look for the headquarters that presides over its rationality. Neither the caste which governs, nor the groups which control the state apparatus, nor those who make the most important economic decisions direct the entire network of power that functions in a society and makes it function. The rationality of power is characterized by tactics that are often quite explicit at the restricted level where they are inscribed... tactics which, becoming connected to one another, attracting and propagating one another but finding their base of support and their condition elsewhere end by forming comprehensive systems. The logic is perfectly clear, the aims decipherable. And yet it is often the case that no one is there to have invented them and few who can be said to have formulated them."

Foucault's interpretation of power raises several important questions. If no individual is completely responsible for how society functions, why is society the way it is? If nobody is fully in control, can anybody be held accountable for some individuals' discomfort or sufferings? We wouldn't blame people for their own misfortunes, would we? If nobody is in control, how can we hope to change things? Can we change things?? These are some of the questions that I attempt to answer with my own theory of power.

SOURCES:

Foucault, M. (2012/1976). The history of sexuality: An introduction. (Trans. by R. Hurley).

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (last updated August 5, 2022). Michel Foucault.

If you are interested in getting updates about this project (e.g., when new pages are published), please sign up for the newsletter on my main website.

THIS WEBSITE CONTAINS NO AI-GENERATED CONTENT

- About

- Introduction

-

Browse the book

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- A >

- B >

- C >

- D >

- E >

- F >

- G >

- H >

- I >

- L >

-

M

>

- Main theories of power

- Making an effort is a prerequisite of using power

- Marxism and the meaning of power

- "May" power

- Meanings of power that are not directly related to social power

- Micropower: Individual power

- Mindfulness

- Media and Digital Literacy as Forms of Individual Power

- (Mis)understanding of power in media texts

- Money and Power

- My synesthetic perception of "power"

- N >

- P >

- R >

- S >

- T >

- U >

- V >

- W >

- Completed pages

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- Author