- About

- Introduction

-

Browse the book

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- A >

- B >

- C >

- D >

- E >

- F >

- G >

- H >

- I >

- L >

-

M

>

- Main theories of power

- Making an effort is a prerequisite of using power

- Marxism and the meaning of power

- "May" power

- Meanings of power that are not directly related to social power

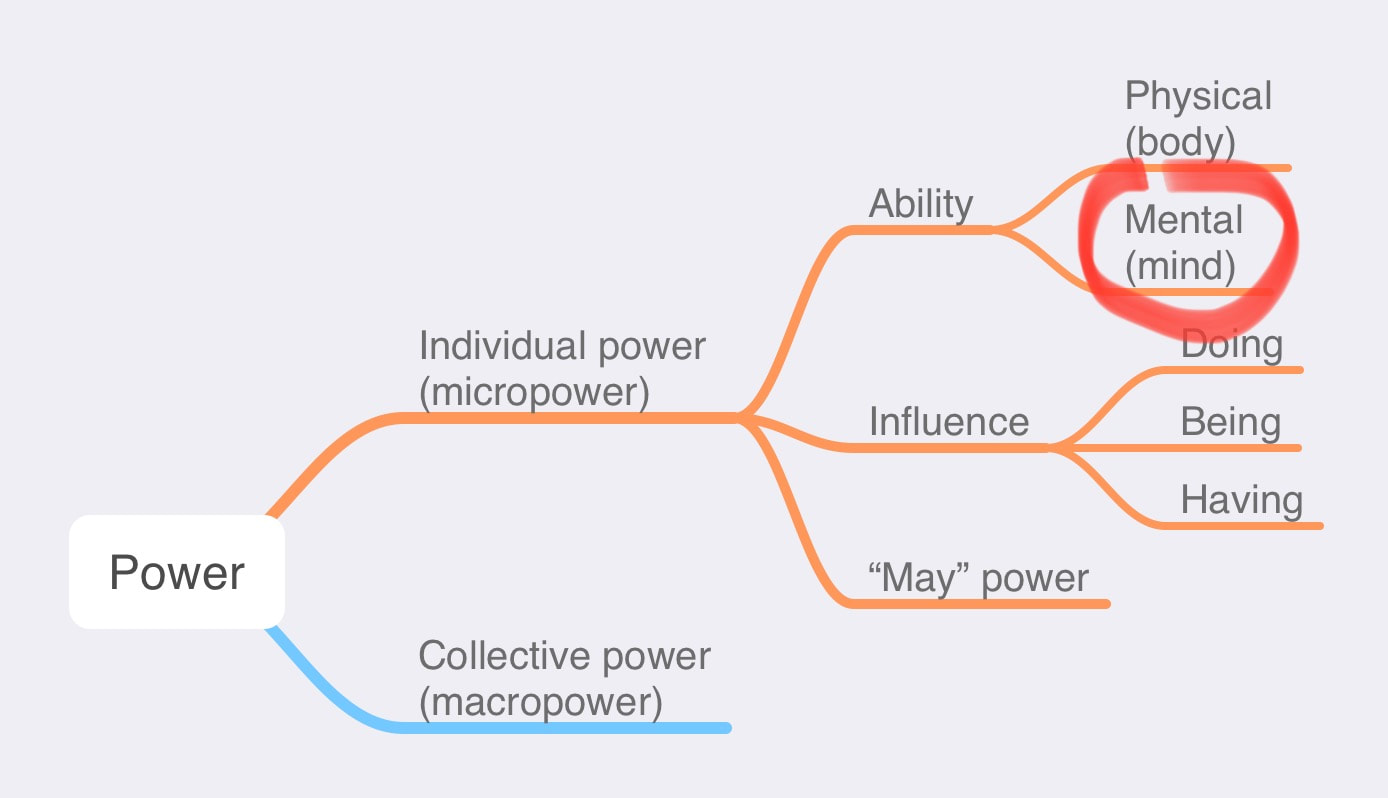

- Micropower: Individual power

- Mindfulness

- Media and Digital Literacy as Forms of Individual Power

- (Mis)understanding of power in media texts

- Money and Power

- My synesthetic perception of "power"

- N >

- P >

- R >

- S >

- T >

- U >

- V >

- W >

- Completed pages

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- Author

Mental Power

PAGE IN PROGRESS

What you see here is a page of my hypertext book POWER of meanings // MEANINGS of power. Initially empty, this page will slowly be filled with thoughts, notes, and quotes. One day, I will use them to write a coherent entry, similar to these completed pages. Thank you for your interest and patience!

What you see here is a page of my hypertext book POWER of meanings // MEANINGS of power. Initially empty, this page will slowly be filled with thoughts, notes, and quotes. One day, I will use them to write a coherent entry, similar to these completed pages. Thank you for your interest and patience!

Power to enjoy the moment

Power to change how you see things

Power to improve your mood

It could always be worse, the story about the goat; power of changing our perspective

Power of kind: to compartmentalize (for example when you listen to a friend who is depressed: how to be empathetic but not be impacted by their worldview- what I asked my councilor at Temple, how can she listen to people sharing their pain and not start feeling depressed)

Self-regulation , ability, a form of power

Can’t help it, tumbling, falling in love” - do we have power over this? Realizing one’s power requires self-awareness

Body/mind duality

AI Mirror chapter 3:

"You might ask, “How can we be so sure that AI tools are not minds? What is a mind anyway?” We have a lot of scientific data about minds, and a few thousand years of philosophical intuitions about them. In terms of a tidy scientific definition, it’s true that we are unfortunately not much closer today than we were in 1641, when the philosopher and mathematician René Descartes defined a mind as “a thinking thing.” Still, based on the scientific evidence, most of us accept that minds are in some way supervenient on the physical brain. That is, minds depend upon the brain for their reality. Minds are unlikely to be free-floating intangibles merely tethered to the body like a pilot to its ship, a metaphor Descartes invoked but ultimately rejected as unsuitable.

Instead, minds almost certainly come into existence through the body and its physical operations. The operations that take place in the brain are essential, but the scientific evidence is increasingly clear that our mental lives are driven by other bodily systems as well: our motor nerves, the endocrine system, even our digestive system. Our minds are embodied rather than simply connected to or contained by our bodies. Descartes got closest to the truth when he admitted that our minds are mysteriously “intermingled” with the body. Unlike a person remotely piloting a ship, it is I, not simply my vehicle, who can be wounded by a violent collision. I don’t move my body around, I move myself.

But Descartes, who was convinced that the mind and body had two separate natures, still could not accept that the mind is truly of the body—that we move and think as minded bodies and embodied minds. He could not have accepted a scientific reality in which the mind is not only the neurons in my brain and nerves in my fingers, but also the hormones flowing in my blood, and the neurotransmitters produced by the bacteria in my gut. A single trained AI model can pilot a swarm of drones or a thousand different robot bodies at once, but I do not pilot my body. I am my body. While something like a soul that survives the body is beyond the reach of science to confirm or refute, to think of my mind—driven by my hormones and nerve signals, moved by the neurotransmitter flows across synapses between my brain and gut neurons—as something other than my body is to commit what philosophers call a category error.[i]

[i] Other kinds of minds are embodied differently, of course. Cephalopods such as octopuses, for example, may have stronger local “minds” in their individual arms, which are only very loosely coordinated by a central intellect. <<<REFO:BK>>>Peter Godfrey-Smith’s Other Minds (2016)<<<REFC>>> offers a fascinating reflection on the uniqueness of cephalopod intelligence and its relation to their distinct environment and morphology.

"

AI Mirror, chapter 3

"Carroll’s work is beloved by every generation because it embodies with rare intensity a humane virtue that is deeply cherished but, for many of us, hard to hold onto. It both exemplifies and glorifies the creative power of human imagination. Imagination is one of the few virtues that we often find more actively and readily expressed in children than adults. A virtue is an excellence of character, a trait that humans treasure and recognize as not only worthy of praise in an individual, but essential to shared human flourishing. There are moral virtues (such as courage, honesty, and generosity) and intellectual virtues (such as wisdom, curiosity, and open-mindedness), although some hold that these two types are not truly distinct.Virtues have been studied by philosophers for millennia, and in many different philosophical traditions and regions of the world. Both the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle and the classical Chinese philosopher Kongzi (widely known by his Latinized name, Confucius) believed that virtues are not innate but acquired by practice. We can think of virtues as our moral and intellectual muscles, which like physical muscles must be actively cultivated and strengthened by activity. So, most of our valued traits, like honesty and courage, are only weakly present as dispositions in children, while some virtues, like wisdom, are thought to be virtually absent in the very young. It is only with many years of reinforcement by habitual moral or intellectual practice, and refinement by social learning and feedback, that a good trait becomes deeply ingrained in our character and shaped well enough to be reliably expressed in the right ways."

When you hear the phrase "mental power", you might imagine a superhero focusing her mental energy in order to move an object telepathically. I am not referring to anything special like that. I believe that all of us have some mental power, which is an ability to do things using our mind.

Mental power is often associated with willpower. Willpower is defined as "control exerted to do something or restrain impulses". On the page dedicated to willpower I discuss why this type of power is considered to be nonexistent by some behavioural scholars. While controlling our impulses by restraining them is a losing fight, this does not mean that we cannot use our mental power to modify our behavior that would be beneficial for us and for people around us.

According to my interpretation of power, it requires intentionality. Which means that we need to distinguish between abilities that we use with awareness and while making a choice vs. functions of our brain, which is something that our brain does automatically because we are human beings.

Using mental power typically requires some effort (we make a choice to make the effort) and awareness about our choice. In fact, making true choices is in itself a form of power.

Depending on whether you think that mind is merely a function of your body or not, you can see this division as artificial — or not. This is a big topic that deserve as separate discussion. Let’s just say that we divide them for the purpose of this analysis.

The most well known power of mind is intelligence. Controversies about intelligence test

multiple intelligences (Gardner)

From AI Mirror, Chapter 2:

"In truth, no single test or benchmark for AI has been endorsed by scientific consensus. This is also true of intelligence itself, which most experts today regard as a “cluster concept” composed of multiple distinct cognitive faculties, rather than a single measurable quality. This is one reason why intelligence tests and related concepts like IQ have long been critiqued as arbitrary, biased, and limited in scope. As the paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould noted in The Mismeasure of Man, the concept of intelligence is tainted by its ties to pseudo-scientific efforts in the 19th century to design a metric that would definitively establish the innate superiority of white European peoples, and thereby justify policies of colonial repression, exclusion, and eugenics."

Michio Kaku: “Sitting on your shoulders is the most complicated object in the known universe.” Michio Kaku, “Behold the Most Complicated Object in the Universe,” interview by Leonard Lopate. The Leonard Lopate Show, WNYC, February 25, 2014, https://www.wnyc.org/story/michio-kaku-explores-human-brain.

Intelligence as embodied “skillful coping” with the world. Need need intelligence to cope with the world: Dreyfus, Hubert. Skillful Coping: Essays on the Phenomenology of Everyday Perception and Action. Ed. Mark A. Wrathall. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

AI Mirror, chapter 2:

Marcus and others have provided a litany of examples of generative AI models failing to understand what they are saying. For instance, the late 2022 release of ChatGPT stated that it could not predict the height of the first seven-foot-tall President of the United States (or the religion of the first Jewish-American President.) Defenders of AI point out that isolated failures of understanding don’t prove that these tools lack understanding of the tasks they do complete correctly. Humans also mess up requests. We do this all the time! Plus, we can always retrain or fine-tune a model to avoid its previous errors. This is why the deeper cause of these failures—the absence of machine understanding of the world—is the real issue. Admittedly, “understanding” is itself hard to define. What does it mean to understand? What would it take to prove that today’s AI models understand anything about the images and texts they manipulate and create, much less the world that gave rise to those data?

If a robot animated by a large AI model can grab you a glass of whiskey when you ask for one, is that enough to prove that it understands what whiskey is? Or, to understand the meaning of “whiskey,” does an AI system need to know something about the world of which whiskey is a part? Does it need to know what it means to be a liquid? Does it need to know that you can pour whiskey on the floor, but that you can’t reverse the operation? Does it need to know why a glass of whiskey is a useful thing to bring to many a healthy adult on a cold winter evening, but a bad thing to bring to a dog, an infant, a person fighting a fire, or a person on a ventilator? Does an AI system understand what whiskey is if it does not know the difference in smell, taste, or potability between a glass of it, and a glass of brownish rainwater?

Social emotional intelligence

emotional regulation

Understanding as power (form of intelligence)

understanding others (empathy; levels of empathy: function - I feel sad when I see someone crying; higher level - trying to understand other if your dislike them)

power to wait; delayed gratification; my 4.5 year old son saying: “I don’t want to wait every day!”

self-awareness

understanding and managing your emotions (emotional regulation)

ability to see that meanings we attach to an object, person, situation are not absolute

ability to see a situation differently or acknowledge that it can be seen differently

power to change the way you see things

power to choose meanings that you focus on

When we think about mental abilities, we imagine intelligence. However, considerable disagreements exist on what counts as intelligence, as debates about the IQ test reveal. Some note that people have multiple intelligences, while others disagree. Debates have raged about mental abilities related to different spheres of life. Are women better at empathy while men are better at math? Two other well-known mental abilities are logic or memory, none of them simple or straightforward.

Other mental abilities may not even have specific names. This does not mean that they are less important, but rather that they are less understood or valued. For example, there is no word (in the languages that I know, at least) for an ability to choose a certain interpretation of a situation or an ability to react to circumstances in one way rather than another. However, arguments are made about the importance of these abilities for our well-being (see Mindfulness, Buddhism).

Same as with physical abilities, one can explore different levels of mental abilities, ranging from a function to a consciously-owned skill that can be improved. For example, we can talk about biases as functions of our brains (Level 1) that are indispensable for being human. We can become aware of these biases and of how they can cause problems (Level 2). Finally, although we cannot get rid of our biases, we can train ourselves not to allow them shape all our reactions (Level 3).

Recognizing how intentionality affects our mental abilities allows us to work on improving these abilities. Improving our mental abilities can itself become a source of power. However, since mental abilities are so difficult to name and classify, it is not yet clear which ones we can/should improve and to what extent.

Power to change how you see things

Power to improve your mood

It could always be worse, the story about the goat; power of changing our perspective

Power of kind: to compartmentalize (for example when you listen to a friend who is depressed: how to be empathetic but not be impacted by their worldview- what I asked my councilor at Temple, how can she listen to people sharing their pain and not start feeling depressed)

Self-regulation , ability, a form of power

Can’t help it, tumbling, falling in love” - do we have power over this? Realizing one’s power requires self-awareness

Body/mind duality

AI Mirror chapter 3:

"You might ask, “How can we be so sure that AI tools are not minds? What is a mind anyway?” We have a lot of scientific data about minds, and a few thousand years of philosophical intuitions about them. In terms of a tidy scientific definition, it’s true that we are unfortunately not much closer today than we were in 1641, when the philosopher and mathematician René Descartes defined a mind as “a thinking thing.” Still, based on the scientific evidence, most of us accept that minds are in some way supervenient on the physical brain. That is, minds depend upon the brain for their reality. Minds are unlikely to be free-floating intangibles merely tethered to the body like a pilot to its ship, a metaphor Descartes invoked but ultimately rejected as unsuitable.

Instead, minds almost certainly come into existence through the body and its physical operations. The operations that take place in the brain are essential, but the scientific evidence is increasingly clear that our mental lives are driven by other bodily systems as well: our motor nerves, the endocrine system, even our digestive system. Our minds are embodied rather than simply connected to or contained by our bodies. Descartes got closest to the truth when he admitted that our minds are mysteriously “intermingled” with the body. Unlike a person remotely piloting a ship, it is I, not simply my vehicle, who can be wounded by a violent collision. I don’t move my body around, I move myself.

But Descartes, who was convinced that the mind and body had two separate natures, still could not accept that the mind is truly of the body—that we move and think as minded bodies and embodied minds. He could not have accepted a scientific reality in which the mind is not only the neurons in my brain and nerves in my fingers, but also the hormones flowing in my blood, and the neurotransmitters produced by the bacteria in my gut. A single trained AI model can pilot a swarm of drones or a thousand different robot bodies at once, but I do not pilot my body. I am my body. While something like a soul that survives the body is beyond the reach of science to confirm or refute, to think of my mind—driven by my hormones and nerve signals, moved by the neurotransmitter flows across synapses between my brain and gut neurons—as something other than my body is to commit what philosophers call a category error.[i]

[i] Other kinds of minds are embodied differently, of course. Cephalopods such as octopuses, for example, may have stronger local “minds” in their individual arms, which are only very loosely coordinated by a central intellect. <<<REFO:BK>>>Peter Godfrey-Smith’s Other Minds (2016)<<<REFC>>> offers a fascinating reflection on the uniqueness of cephalopod intelligence and its relation to their distinct environment and morphology.

"

AI Mirror, chapter 3

"Carroll’s work is beloved by every generation because it embodies with rare intensity a humane virtue that is deeply cherished but, for many of us, hard to hold onto. It both exemplifies and glorifies the creative power of human imagination. Imagination is one of the few virtues that we often find more actively and readily expressed in children than adults. A virtue is an excellence of character, a trait that humans treasure and recognize as not only worthy of praise in an individual, but essential to shared human flourishing. There are moral virtues (such as courage, honesty, and generosity) and intellectual virtues (such as wisdom, curiosity, and open-mindedness), although some hold that these two types are not truly distinct.Virtues have been studied by philosophers for millennia, and in many different philosophical traditions and regions of the world. Both the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle and the classical Chinese philosopher Kongzi (widely known by his Latinized name, Confucius) believed that virtues are not innate but acquired by practice. We can think of virtues as our moral and intellectual muscles, which like physical muscles must be actively cultivated and strengthened by activity. So, most of our valued traits, like honesty and courage, are only weakly present as dispositions in children, while some virtues, like wisdom, are thought to be virtually absent in the very young. It is only with many years of reinforcement by habitual moral or intellectual practice, and refinement by social learning and feedback, that a good trait becomes deeply ingrained in our character and shaped well enough to be reliably expressed in the right ways."

When you hear the phrase "mental power", you might imagine a superhero focusing her mental energy in order to move an object telepathically. I am not referring to anything special like that. I believe that all of us have some mental power, which is an ability to do things using our mind.

Mental power is often associated with willpower. Willpower is defined as "control exerted to do something or restrain impulses". On the page dedicated to willpower I discuss why this type of power is considered to be nonexistent by some behavioural scholars. While controlling our impulses by restraining them is a losing fight, this does not mean that we cannot use our mental power to modify our behavior that would be beneficial for us and for people around us.

According to my interpretation of power, it requires intentionality. Which means that we need to distinguish between abilities that we use with awareness and while making a choice vs. functions of our brain, which is something that our brain does automatically because we are human beings.

Using mental power typically requires some effort (we make a choice to make the effort) and awareness about our choice. In fact, making true choices is in itself a form of power.

Depending on whether you think that mind is merely a function of your body or not, you can see this division as artificial — or not. This is a big topic that deserve as separate discussion. Let’s just say that we divide them for the purpose of this analysis.

The most well known power of mind is intelligence. Controversies about intelligence test

multiple intelligences (Gardner)

From AI Mirror, Chapter 2:

"In truth, no single test or benchmark for AI has been endorsed by scientific consensus. This is also true of intelligence itself, which most experts today regard as a “cluster concept” composed of multiple distinct cognitive faculties, rather than a single measurable quality. This is one reason why intelligence tests and related concepts like IQ have long been critiqued as arbitrary, biased, and limited in scope. As the paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould noted in The Mismeasure of Man, the concept of intelligence is tainted by its ties to pseudo-scientific efforts in the 19th century to design a metric that would definitively establish the innate superiority of white European peoples, and thereby justify policies of colonial repression, exclusion, and eugenics."

Michio Kaku: “Sitting on your shoulders is the most complicated object in the known universe.” Michio Kaku, “Behold the Most Complicated Object in the Universe,” interview by Leonard Lopate. The Leonard Lopate Show, WNYC, February 25, 2014, https://www.wnyc.org/story/michio-kaku-explores-human-brain.

Intelligence as embodied “skillful coping” with the world. Need need intelligence to cope with the world: Dreyfus, Hubert. Skillful Coping: Essays on the Phenomenology of Everyday Perception and Action. Ed. Mark A. Wrathall. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

AI Mirror, chapter 2:

Marcus and others have provided a litany of examples of generative AI models failing to understand what they are saying. For instance, the late 2022 release of ChatGPT stated that it could not predict the height of the first seven-foot-tall President of the United States (or the religion of the first Jewish-American President.) Defenders of AI point out that isolated failures of understanding don’t prove that these tools lack understanding of the tasks they do complete correctly. Humans also mess up requests. We do this all the time! Plus, we can always retrain or fine-tune a model to avoid its previous errors. This is why the deeper cause of these failures—the absence of machine understanding of the world—is the real issue. Admittedly, “understanding” is itself hard to define. What does it mean to understand? What would it take to prove that today’s AI models understand anything about the images and texts they manipulate and create, much less the world that gave rise to those data?

If a robot animated by a large AI model can grab you a glass of whiskey when you ask for one, is that enough to prove that it understands what whiskey is? Or, to understand the meaning of “whiskey,” does an AI system need to know something about the world of which whiskey is a part? Does it need to know what it means to be a liquid? Does it need to know that you can pour whiskey on the floor, but that you can’t reverse the operation? Does it need to know why a glass of whiskey is a useful thing to bring to many a healthy adult on a cold winter evening, but a bad thing to bring to a dog, an infant, a person fighting a fire, or a person on a ventilator? Does an AI system understand what whiskey is if it does not know the difference in smell, taste, or potability between a glass of it, and a glass of brownish rainwater?

Social emotional intelligence

emotional regulation

Understanding as power (form of intelligence)

understanding others (empathy; levels of empathy: function - I feel sad when I see someone crying; higher level - trying to understand other if your dislike them)

power to wait; delayed gratification; my 4.5 year old son saying: “I don’t want to wait every day!”

self-awareness

understanding and managing your emotions (emotional regulation)

ability to see that meanings we attach to an object, person, situation are not absolute

ability to see a situation differently or acknowledge that it can be seen differently

power to change the way you see things

power to choose meanings that you focus on

When we think about mental abilities, we imagine intelligence. However, considerable disagreements exist on what counts as intelligence, as debates about the IQ test reveal. Some note that people have multiple intelligences, while others disagree. Debates have raged about mental abilities related to different spheres of life. Are women better at empathy while men are better at math? Two other well-known mental abilities are logic or memory, none of them simple or straightforward.

Other mental abilities may not even have specific names. This does not mean that they are less important, but rather that they are less understood or valued. For example, there is no word (in the languages that I know, at least) for an ability to choose a certain interpretation of a situation or an ability to react to circumstances in one way rather than another. However, arguments are made about the importance of these abilities for our well-being (see Mindfulness, Buddhism).

Same as with physical abilities, one can explore different levels of mental abilities, ranging from a function to a consciously-owned skill that can be improved. For example, we can talk about biases as functions of our brains (Level 1) that are indispensable for being human. We can become aware of these biases and of how they can cause problems (Level 2). Finally, although we cannot get rid of our biases, we can train ourselves not to allow them shape all our reactions (Level 3).

Recognizing how intentionality affects our mental abilities allows us to work on improving these abilities. Improving our mental abilities can itself become a source of power. However, since mental abilities are so difficult to name and classify, it is not yet clear which ones we can/should improve and to what extent.

Image credit: A frame in motion

If you are interested in getting updates about this project (e.g., when new pages are published), please sign up for the newsletter on my main website.

THIS WEBSITE CONTAINS NO AI-GENERATED CONTENT

- About

- Introduction

-

Browse the book

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- A >

- B >

- C >

- D >

- E >

- F >

- G >

- H >

- I >

- L >

-

M

>

- Main theories of power

- Making an effort is a prerequisite of using power

- Marxism and the meaning of power

- "May" power

- Meanings of power that are not directly related to social power

- Micropower: Individual power

- Mindfulness

- Media and Digital Literacy as Forms of Individual Power

- (Mis)understanding of power in media texts

- Money and Power

- My synesthetic perception of "power"

- N >

- P >

- R >

- S >

- T >

- U >

- V >

- W >

- Completed pages

-

All the pages alphabetically

>

- Author